It was shortly after dawn when Alec Ramsay walked into the training barn at Hopeful Farm and found the new employee man-handling Black Sand. He ran into the stall and caught the man's foot as it swung hard toward Black Sand's belly. Once he had hold of it, Alec heaved backward, upsetting the man and putting him down in the straw.

"I told you never to rough up these colts," Alec shouted angrily. "Now get out of here."

The man lay still, his jaws and eyes open, breathing heavily. "That crazy colt bit me," he said. His fingers tightened about the bridle in his hands as if he were about to swing it at Black Sand's head.

Alec moved the colt back, knowing the ex-jockey had been drinking and it would not be easy to get rid of him.

"That's still no reason to hit him," Alec said. "You're through."

The man attempted to get up, the big muscles of his shoulders bunching. "Give me another chance, Alec," he pleaded. "It won'thappen again."

Alec didn't believe him. The tone of his voice was all wrong, just as his apology was meaningless. "I hired you knowing you drank," Alec said. "You knew I knew. You promised it wouldn't happen here. I said I'd give you one chance, but only one, because nobody else in the business would hire you."

"I know," the man said, his voice surly. "You don't have to give me any rundown."

"Then you know why I'm not giving you another chance," Alec said. "Get up. I'll make out your check and you can get out of here."

The man raised a hand, big and rough and grimy, asking for Alec's help in rising. He seemed unsteady; as if he couldn't make it alone.

Alec hesitated before reaching out. The ex-jockey was in his mid-forties, no taller than he but more heavily built in the shoulders and with all the strength that came from many years of racing horses. Alec decided he had to take a chance; he had to get him out of the stall where he could do no harm to the colt.

The man was in a half-crouch when their hands met. Without any warning, he swung the bridle hard. Alec deflected the steel bit but the leather reins lashed his face. Then the man's hurtling body was on top of him, hands tearing at his eyes and head. As Alec fell, he managed to swing a booted foot, catching his opponent in the knees and sending him sprawling beside him. He rolled over and chopped hard at the man's throat with the side of his hand.

The man gasped for breath, but he straightened and swung violently upward, with Alec clinging to his back. They went reeling backward to fall in the straw with Alec on the bottom.

Alec twisted, avoiding the man's elbows, which sought to batter his head and face; then he got in several swift punches of his own that knocked his opponent off him. Quickly, he scrambled to his feet and struck at the man's right wrist with the side of his hand. There was a cry of pain as the man fell back gasping, his wrist dangling brokenly.

"Enough," he whimpered.

Alec shoved him out of the stall and followed him to the apartment on the second floor of the barn. It was a mess with empty wine and liquor bottles everywhere, dirty dishes and glasses piled high, soiled clothes and bed linen--and the man had occupied it less than a week.

"Pack up," Alec said. "I'll wait and take you to the hospital. You need help for more than your wrist."

"Not me, you won't," the ex-jockey said. "You're not takin' me to no hospital. Just give me my check and I'll get out of here."

Later, with the man gone, Alec returned to his office and read the advertisement he had been running in all horse publications for the past six months.

WANTED: Reliable man for stable on race-horse farm. Must have professional experience handling and riding young horses. Must be of good character. Must provide references. Good wages with furnished apartment and fringe benefits. Write Hopeful Farm, Box 37, Millville, N.Y.

The advertisement had not been very successful. Alec had hired several men for the job but none had been reliable. Good help was hard to get and even more difficult to keep.

Hopeful Farm was an incorporated business with his parents and Henry Dailey, the trainer, as the principal stockholders. Officially, his own position was that of stable rider, since one could not own and ride a race horse. However, while his parents lived on the farm and his father was responsible for the hiring of local help for maintenance work, Alec was in charge of finding the professional horseman to break and school the two-year-olds. He couldn't handle the colts himself, for he and Henry Dailey had begun a long summer of racing their great champion, the Black Stallion, in New York City. But occasionally Alec got a few days off and returned home, helping his father supervise the tremendous amount of work involved in running the farm.

Frustrated and impatient, Alec went to the window that overlooked the separate paddocks where the two-year-olds were grazing and playing on the best grass that could be grown. Black Sand was among them and clearly enjoying his freedom. If he could not get the man he needed, Alec decided, it would be far better to turn out the young stock until he and Henry had time to handle it.

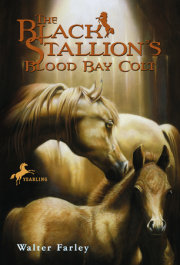

Alec watched the horses. Some of them were unsteady on theirlegs, trying to find their balance, but they were all of a dazzling and powerful beauty. Their long, thick manes and fine coats--black, bay, chestnut and gray--had the gleam of wild silk in the early morning sun. Their deep shoulders and chests and muscular, arched necks breathed forth inexhaustible strength, endurance and spirit. They would be horses to reckon with on the race track, he knew. The future of Hopeful Farm rested on their young backs.

Beyond, in an adjacent field, grazed the heavy but loving mares with suckling foals at their sides. They, too, would help determine the future of Hopeful Farm.

Copyright © 2009 by Walter Farley. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.