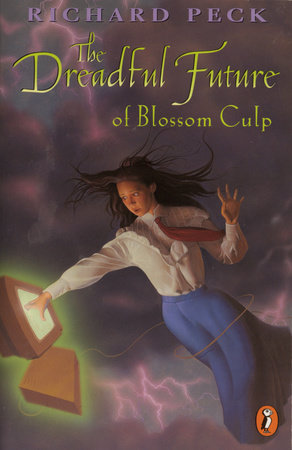

Time warp

Lightning split the air, traveling down the rods on the roof. It clamped my hand to the doorknob. I couldn’t turn loose or turn back now. My skin sizzled, and the door blew in, jerking me half out of my boots.

Inside, the light like a white fog peeled my eyeballs and took me prisoner. The sounds I’d heard in the distance were clearer and nearer: the pyongs and the beeps alike. They were no noise of nature or the human voice. . . .

“Comedy is a strong point. . . . Scenes will have readers laughing out loud.”

—Booklist

BOOKS BY RICHARD PECK

Amanda/Miranda

Are You in the House Alone?

The Dreadful Future of Blossom Culp

Father Figure

The Great Interactive Dream Machine

The Ghost Belonged to Me

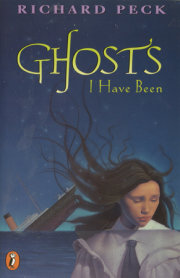

Ghosts I Have Been

A Long Way from Chicago

Lost in Cyberspace

Strays Like Us

A Year Down Yonder

RICHARD PECK

Table of Contents

1

UNLESS YOU NEVER GOT OUT OF GRADE SCHOOL, you’ll have noticed how life keeps making you start over.

In the year of 1914 my class went from being eighth graders at Horace Mann School to being freshmen at Bluff City High School, which is just across the road. Being the youngest and newcomers over there, we were all regarded as lower than a snake’s belly. I don’t know who sets such rules. My name is Blossom Culp, and I live by rules of my own.

I’ve been looked down on before, plenty, so turning into a freshman didn’t hit me as hard as some I could mention. Letty Shambaugh liked to die of shame. She’s lived all her fourteen-plus years with her nose in the air, her paw being the owner of the Select Dry Goods Company.

On the other hand, the last time my paw showed his face in Bluff City, my mama run him out of town. Above her head Mama waved an empty blended whiskey bottle, the blended whiskey itself being in Paw. Though she could outrun him sober, she kept just at his heels to the city limits.

I only mention this to show the difference between me and Letty Shambaugh. Her mama can keep her paw in line with one hand while running the Daughters of the American Revolution with the other.

Letty lives in the lap of luxury in a large all-brick house on Fairview Avenue, famous far and wide for its good taste. My mama and me occupy a two-room dwelling by the streetcar tracks just behind the Armsworths’ barn. Though Mama and me have made improvements on it, every election year some candidate or other promises the voters he’ll have our place demolished in the interest of progress.

Never mind. The world is full of Letty Shambaughs, and this includes the high school. But there is only one Blossom Culp, and I am her.

That’s more or less what Miss Mae Spaulding said to me on the last day of school. Miss Spaulding is both eighth-grade teacher and principal of Horace Mann, being not only a very learned woman but well organized.

When Miss Spaulding called me into her office, Letty Shambaugh and all her little club of girls pointed their fingers at me and hooted.

Letty, looking shapeless in her shell-pink graduation dress with a big corsage stuck to her shoulder, twitched her elbows and said, “I expect Miss Spaulding has bad news for Blossom. I have an idea Blossom is to be held back.”

All the girls in her club, which is called the Sunny Thoughts and Busy Fingers Sisterhood, agreed with her, like they’re supposed to.

I didn’t dignify this charge with a reply. There was no earthly reason I’d be held back to repeat eighth grade. Nobody would. It was clear that Miss Spaulding had had enough of all of us, which is more or less what she said to me.

If you’ve ever been summoned to a principal’s office, you know the feeling. Decorating Miss Spaulding’s wall are a bust of the poet Longfellow, a portrait of President Woodrow Wilson, and a well-worn paddle. I’d been in there before, and there’s nothing homelike about it.

Though Miss Spaulding has no more figure than a runner bean, she makes up for it with posture. But on that day she was somewhat bent, as teachers get toward the end of a school year.

It had been a busy afternoon. We’d had the handing out of diplomas, several speeches, and the traditional maypole dance. Then we said the Pledge of Allegiance one last time and called it a day.

It had all tired Miss Spaulding worse than regular routine, and I hadn’t seen much point to it myself. She settled into her desk chair and seemed to wilt.

“Well, Blossom, we have lived to see this graduation day.”

Yes, ma’am.”

“You and I have had our little differences over the years, have we not?”

I nodded, recalling several.

“Without checking the records,” she said, “I believe I saw you first in this office in fourth grade.”

“Yes, ma’am. That was the year me and my mama moved up here from Sikeston. And naming no names, a bunch of girls dragged me into the rest room and pretty nearly took me apart.”

Miss Spaulding sighed. “I am afraid, Blossom, it was something you must have said that . . . excited their curiosity.”

“Oh, well, shoot,” I said. “Any little thing will set them off.”

“Then along about sixth grade,” she continued, “there was that blue racer snake that Maisie Markham found in her lunch bucket. The poor child actually put her hand on that thing, thinking it was liverwurst sausage. You will recall how the experience affected her digestion.”

I remembered clearly. Anybody would. “She’s gained all that weight back since and then some.”

“The culprit, however, has never been brought to justice.”

“It wasn’t me,” I said.

“It wasn’t I,” Miss Spaulding said.

“I never thought it was.”

She sighed deeper. “What is past is past, I suppose. But I wonder if much progress has been made. I refer to the maypole dance today.”

She was closing in on me fast. But this is America, so I hoped to have a chance to defend myself.

“I am not referring to your dress, Blossom. Never think it.”

Letty Shambaugh had decreed that all the girls should wear shell-pink, made up of yardage purchased at her paw’s Select Dry Goods store. I was hanged if I’d go along with that. I wore my gray princess dress, which there is still some wear in. On my chest I planted my spelling medal. I’m a champion speller, which comes in handy in die writing of this true account.

I even perked up my outfit with a new purple sash, which was as far as I’d go. There was nothing to be done about my hair, which kinks in this weather.

“I am referring to the maypole dance itself,” Miss Spaulding said, “after all those rehearsals that went so well. How long did we rehearse our dance, Blossom?”

“Every dadburned night for a week,” says I, “weaving them ribbons around that pole, with Letty Shambaugh bossing us all like she was—”

“It would have been a lovely spectacle,” Miss Spaulding said, “so graceful with all the ribbons making pretty patterns. But it was not to be, was it?”

“Fate moves in mysterious ways,” I said.

“Who, Blossom, do you suppose went to all the work of digging around the maypole in the dead of last night and undermined its foundations? Who so unbalanced the pole that one sharp tug on a ribbon would bring the whole pole crashing down, barely missing Ione Williams’s head and grazing Letty’s corsage? Who, for that matter, gave a ribbon the sharp tug? I grant you, it made all the boys laugh, if that was the intention.”

“Anything will make a boy laugh,” I said. It was a regular scandal how the finger of blame always pointed my way when any little thing went wrong.

“But we must let bygones be bygones.” Miss Spaulding sighed. She’d waved me into a chair, and there I sat, swinging my legs, waiting for her to come to her main point, which she always does.

“Next September, Blossom, you will be across the road at the high school. This is a first-rate opportunity, if you will but take it, to make a fresh start with a clean slate. You will find high school very different. It would be fortunate if high school did not find you so . . . different. Do you follow me?”

I thought I did. “Lay low and keep my nose clean?”

Miss Spaulding looked pained. “In so many words, yes. Blossom, you are growing up and beginning to become a young . . . lady. Anytime now your . . . form may begin to fill out.”

She looked down at her own form, which never has, and cleared her throat. “You will develop . . . new interests, such as your personal appearance and daintier habits.”

I wiped my nose on my sleeve and wished she’d come to her point without going all around Robin Hood’s barn. She can be very plainspoken if she tries.

“In short, Blossom, I think it would be better for you and the community at large if you put some of your old habits to rest. There are better ways of getting attention than dabbling in the . . . occult.”

“If you mean my Second Sight,” I said, “it’s no prank, like the snake in Maisie’s lunch or the maypole—whoever pulled them stunts. It’s a Gift, and it’s in the blood. I get it from my mama, who is seven-eighths Gypsy. Mama could take a squint at your tea leaves, Miss Spaulding, and read your whole future like a book.”

“That won’t be necessary,” she replied. “I know my future.”

“You do?”

She nodded. “Once you are across the road at the high school, my future will be smooth sailing. I look forward to some much deserved peace and quiet.”

“Mama could give you a closer reading than that,” I said. “Mama could pinpoint the hour of your death to a minute!”

Miss Spaulding flinched. “Blossom, there are people who do not want the hour of their deaths . . . pinpointed. There are people who think all this . . . spiritualism is hogwash.”

“They’re ignorant.”

“Nevertheless”—Miss Spaulding straightened several small items on her desk—“it’s high time you learned how to get along in this world without worrying about . . . other locations.”

“When the fit comes over me and I get my Vibrations, seems like I don’t have much say in the matter. You remember yourself, Miss Spaulding, that time right here in this office when I had one of my spells. I was here and elsewhere all at once. You sat right there and watched my spirit wander back in time until I found myself aboard the steamship Titanic just when it took its fatal—”

“Please, Blossom.” Miss Spaulding put out her hand like a crossing guard. “You need not refresh my memory. The event is still vivid in my mind. I have given your . . . experiences long thought, and I have come to the only possible conclusion, a scientific conclusion.”

She paused. “You will have heard the term ‘puberty,’ Blossom?”

The term rang a bell with me, but I couldn’t exactly put my finger on it. Miss Spaulding’s face had gone beet-red. She cleared her throat a number of times, rapid-fire.

“Puberty is that time of life when a young girl begins to become . . . an older girl. It is a time of considerable . . . upheaval to body and brain alike. I have concluded that your . . . psychic episodes were purely a temporary condition. Do you comprehend my meaning?”

“I can see ghosts, too,” I told her.

Miss Spaulding wilted more till her chin was on her chest. You never saw a tireder woman. Trying to help her out, I said, “You mean, I was going through a stage and now I’m beginning to outgrow it?”

She perked up. “Precisely, Blossom! Put your past behind you and all your . . . exploits. Over at the high school they like team players. I’m sure you can settle down and be one if you put your mind to it.”

“I guess I could try,” I said.

“Try, and you will succeed!” Miss Spaulding sang out. “Do not be tempted, Blossom. If you begin to . . . Vibrate, or whatever it is you do, or if some thoughtless classmate goads you into showing off, turn a deaf ear!”

She heaved herself up from her desk. “Mind over matter, Blossom. Let that be the motto for your future!”

Throughout the summer of 1914 I thought over Miss Spaulding’s advice. I supposed it was possible that I was outgrowing my Second Sight. Mama always says my Powers are puny compared to hers, though she’s the jealous type. I even thought it might be just as well if I was more like other people. I was about half-willing to lay my Powers to rest.

But that’s where Fate stepped in. I was to learn it isn’t possible to turn away from my talents. A Gift is a curse if you don’t put it to work.

As a freshman at Bluff City High School I was often to recall with a wry smile how Miss Spaulding had warned me to look to my future. For I was to set foot into a future world beyond all Miss Spaulding’s scientific conclusions, even beyond the imaginings of any person now living.

I was to see the Dreadful Future firsthand for myself, and as plain as the nose on your face.

2

ON A WARM SEPTEMBER MORNING my route to high school took me around the Armsworth family barn and across their property. My mama economizes on breakfasts, kicking me out of the house early, so on my way I’m always greeted by the smell of frying bacon coming from the Armsworth mansion.

Alexander Armsworth, a kid of my acquaintance, lives there. He can’t help but know me since we’re near neighbors. However, Alexander managed to avoid me all that summer like I had the typhoid fever.

Him and me have reason to be friends, though a boy rarely listens to reason. We’re the only two people in Bluff City with the Second Sight, except for my mama. I get my Gift from her. Where Alexander gets his is anybody’s guess.

Seems like all he does is deny he has it. One time he saw a ghost right there in the loft of the Armsworth barn. Locally that outbuilding is still known as the Ghost Barn because of this famous happening. But it took wild horses to drag a confession out of Alexander.

Let him catch one glimpse of a haunt or some poor restless soul in search of a decent grave, and he turns tail. A boy hates to show fear worse than poison, and when it comes to the Spirit World, Alexander Armsworth is scared of his own shadow. He is girl-shy, too, or at least shy of me.

But he is not bad-looking. I lingered along that morning under the bay window of the Armsworth dining room, hearing the clink of knife and fork and Alexander’s mama whining. But there was no reason to linger, though I kicked a certain amount of gravel. If Alexander spied me from the bay window, he’d take to the cellar till I was off the place. He treats me worse than a ghost.

I slowed again when the high school hove into view. As Bluff City is an up-and-coming place with better than twenty-two hundred inhabitants, they have a first-rate high school.

It was larger than I remembered, and the entire student body was milling around outside, many of them as big as grown-ups. Nearly all the female sex was in long skirts. The boys parted their hair in the middle and gummed it down with grease. Everybody was trying to look like everybody else with much success.

Some that I took to be juniors and seniors were arriving in auto—roadsters and touring cars and such—and the country ones were coming in by the wagonload. The football team showed off by tackling each other on the field out back. It was a sight.

Everybody seemed well acquainted with everybody else, calling out greetings. Though I’m used to going it alone, I wouldn’t have minded knowing someone to call out a greeting to. But the only familiar faces I saw were Letty Shambaugh and her club of girls. They’d congregated around Letty for mutual protection under a shade tree. She seemed to be getting them organized. I don’t look for friendship or even common decency from Letty, so I was willing to pass them by.

But Letty hollered out, “You there, Blossom Culp! I want a word with you.” At that her whole club turned my way.

Ione Williams was there, and Harriet Hochhuth and the Beasley twins, Tess and Bess, who are identical, and Maisie Markham, who stands out a mile.

Letty has the sweetest little face you ever saw until you come to her mouth, which is mean. She bustled up and began to speak. Then her eyes popped when she saw the spelling medal I wore depending from my front.

“Well, if that doesn’t about take the cake!” she exclaimed. “Wearing that old grade school spelling medal to high school!”

“Did you ever?” said several of her club.

“They are not going to be interested in your so-called past achievements here at the high school,” Letty continued. “Take my advice and throw that thing away.”

I made a silent vow right then to wear that spelling medal on my chest until it fell off.

“But never mind about that,” Letty said. “What I want to say to you is this, Blossom. You will find here at the high school they have such a thing as school spirit. The freshman class must pull together, and as Miss Spaulding used to say, ‘A chain is only as strong as its weakest link.’”

Letty left no doubt as to who the weakest link was, and all her club looked right at me.

“We don’t have any intention in this world of being dragged down or embarrassed to death by you, Blossom. Let this be a warning.” Her eyes narrowed to slits.

“Is that a fact,” I remarked.

She patted her hair bow. “You cannot help your background, Blossom, or do much about your looks. But I hope in my heart you won’t make a jackass of us all by telling tall tales and poking your nose into other people’s business and claiming you are some kind of a witch or whatever, which are three of your bad habits.”

There are times in life when it’s better to remain silent and let your fists do the talking. I was winding up to knock the socks off Letty Shambaugh when I caught a glimpse of Alexander Armsworth in the distance, which distracted me.

He was wandering into the schoolyard in a new belted knicker suit with his eyes peeled for two high school cronies of his, Bub Timmons and Champ Ferguson.

Then from within the schoolhouse a bell rang, the first of many. Everybody ganged toward the entrance. Alexander was claimed by Bub and Champ, and Letty singed ahead with all her club. I was left to face high school alone, keeping Alexander Armsworth in the corner of my eye.

I suppose high school is educational, though very little of it is to my taste. The teachers can teach only one subject, so you spend half the day traipsing from one classroom to the next, herded along like hogs in a chute.

To keep us freshmen in our place, we all had to wear what they call beanies, which are little orange and black skullcaps with the number 18 on them, as we are to be the graduating class of 1918. I had to anchor my beanie on my unruly hair with a hatpin.

As headgear they are not flattering, though Letty wore hers like a crown of jewels. On Maisie Markham’s big head, the beanie looked like a covered button. But if you turned up without one, some sophomore had the privilege of wiping the floor with you.

Our days began with a thing they call homeroom. Here attendance is taken and announcements are made. All the freshmen are stuck in the same homeroom, so it was no better than being in Horace Mann School. In the first week we had class elections. Letty was made president of the class, and Alexander was made vice-president. My name didn’t come up.

Our homeroom teacher was an ancient person, name of Miss Blankenship. We returned to her later each day for English literature, where she was driving us with a whip through a play called Hamlet. Every day she put a new quotation from this play on the blackboard, such as:

SOMETHING IS ROTTEN IN THE STATE OF DENMARK

Act I

which was written out in her quavering hand. Until Miss Blankenship, I hadn’t known that a woman can go bald, too. But she wasn’t blind. One false step and she nailed you.

Though I could put up with most of high school, I nearly drew the line at what they call Girls’ Gym. I get all the exercise I need, and I’m not in the habit of taking off my clothes in public. Still, we all had to take it except for Maisie Markham, who was excused on the grounds of weight.

I’d expected the gym teacher to be a big, beefy woman, like a heavyweight wrestler in bloomers. But here I was proved wrong.

Her name was Miss Fuller, and she was more willowy than muscular. She wore a bandeau of flowered silk tight across her forehead and artistic drapings in several colors hanging down over her bloomers. Satin ribbons that attached to her gym shoes crisscrossed to the knee over her cotton stockings. She had a wan face and sad spaniel eyes with a suspicion of rouge dotting both her prominent cheekbones.

Under her direction, we ran relays and swung Indian clubs, but she favored what she called Artistic Expression. She’d crank up an Edison Victrola and play a song called “Pale Hands I Love Beside the Shalimar.” To this accompaniment we were to turn ourselves into fields of waving wheat or sometimes flowers sprouting and putting out foliage.

She was a great one for graceful movement, and I’d often fall down, as I found it hard to maneuver in bloomers and rubber shoes. I wouldn’t have minded it much except for the locker room. Here we had to strip down and shower together in a big galvanized metal enclosure.

. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.