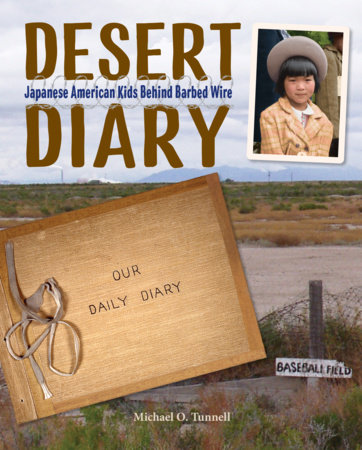

Prologue IN 1943, EIGHT-YEAR-OLD MAE YANAGI stood and recited the Pledge of Allegiance with her classmates. Then, like any other third grader, she began a day of math, reading, and spelling. Mae’s teacher, Miss Yamauchi, always included time for the children to discuss what was happening in school and at home. Afterward she would summarize their words on a piece of art paper—a new page to be added to the class’s daily diary. Mae most likely couldn’t wait for her turn to decorate the day’s diary page with pencil and crayon drawings.

Lots of classrooms keep diaries—but this diary was different. It told the story of a strange and isolated school with children from uprooted families.

As a third grader, Mae might not have fully realized that her school day was anything but normal. Still, she must have understood that “liberty and justice for all” did not apply to her, her classmates, her teacher, or her parents. A year earlier she had attended school in the San Francisco Bay Area. Her classroom was filled with children of many backgrounds, including white children and kids of Japanese American descent. Now nearly every face was Japanese, like her own. And when Mae looked out the window, instead of the green of Northern California, she saw a parched landscape framed by Utah mountains. Instead of regular houses, she saw row after row of what looked like army barracks. Beyond the barracks stood guard towers with searchlights and soldiers carrying rifles—and a barbed-wire fence.

Mae Yanagi, US citizen, was a prisoner.

Chapter 1: Unwanted MAE YANAGI WAS SEVEN YEARS OLD in December 1941, when her life was tipped head over heels. Almost overnight, she and her family found themselves torn from their home in Hayward, California. And they weren’t the only ones forced to leave—anyone with a Japanese face had to go.

By the end of 1942, everyone of Japanese ancestry, or Nikkei (neek-kay), had disappeared from the coastal regions of California, Oregon, and Washington. Most Nikkei from the San Francisco Bay Area ended up in hastily constructed “internment camps”—prison camps enclosed by barbed wire—in the mountain deserts of Utah. Other Americans of Japanese descent were transported away from the West Coast to similar camps in other interior states. But how could this happen in America, the land of the free?

Most first-generation Japanese immigrants, or Issei (ees-say), were on the West Coast, where they faced fierce bigotry. National laws denied them American citizenship. Some states prohibited them from owning land and banned all Nikkei from intermarriage with white Americans.

Despite the prejudice, many Japanese immigrants managed comfortable lifestyles through hard work. Although jobs with white employers were scarce, many Issei started successful businesses. Others turned substandard plots of rented ground into prosperous fruit and vegetable farms. Some even purchased land by placing it in the names of their children, the Nisei (nee-say), who were born in the United States and therefore American citizens.

Often Nikkei worked hard to become “Americanized,” while preserving many of their Japanese cultural traditions. Yoshiko Uchida’s family lived in a three-bedroom bungalow in Berkeley, California. Her family owned a Buick and subscribed to National Geographic. As a grade-schooler, Yoshiko roller-skated and played cops and robbers, just like any other American kid. At the same time her family ate Japanese dishes and kept alive Japanese traditions, such as Hinamatsuri (hee-nah-mah-tsoo-ree), or Doll Festival, a day celebrating girls. Later, in high school, Yoshiko wore stylish clothing and listened to popular music. But the doors to white society were still closed to her and other Nisei teenagers. White employers wouldn’t hire Nisei college graduates. And many white beauty salons wouldn’t even cut Yoshiko’s hair. But all in all, she remembered her life in California as pleasant and happy.

Then, on December 7, 1941, everything changed. Early that morning, Japanese aircraft launched a surprise attack on the US naval base at Pearl Harbor, in Hawaii. Bombs poured down on the unsuspecting base, destroying much of the United States’ Pacific Fleet and killing more than two thousand people. Though World War II was already raging in other parts of the world, Japan’s attack brought America into the conflict.

Suddenly all Nikkei, even those who were American citizens, came under suspicion. Despite a complete lack of evidence, newspapers printed rumors of Nikkei collusion with Japan. One story claimed that “Japs” (the name used for the enemy) in Hawaii had cut arrows in their crops to guide enemy aircraft to the target. Another reported that “Japs” in California planned to sabotage airports, power plants, and other military targets. Not a single case of such traitorous behavior was ever confirmed, but restaurants and stores suddenly refused to serve those of Japanese descent. Tombstones in Japanese cemeteries were smashed. Homes were vandalized. Farmers were terrorized. Mae and Yoshiko found themselves barred from movie theaters, roller rinks, and public parks.

Strident voices of fear and prejudice soon drowned out voices of reason. “I am for immediate removal of every Japanese on the West Coast to a point deep in the interior,” wrote well-known newspaper columnist Henry McLemore. “Let ’em be pinched, hurt, hungry, and dead against it. . . . Personally, I hate the Japanese. And that goes for all of them.” The US Congress strongly supported removing all people of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast, where (it was incorrectly rumored) spies might cooperate with the Japanese military likely lurking in submarines offshore.

In the end, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the army to oust Nikkei from the West Coast and created the War Relocation Authority (WRA) to manage their removal and confinement. It didn’t matter that most of them were American citizens. It didn’t matter that they posed no military threat. The WRA would round up Mae, Yoshiko, and all other people of Japanese ancestry and forcibly move them away from their homes.

Though Mae and her parents knew they would be compelled to leave, it was still a shock to receive removal orders. Yoshiko’s Evacuation Day, or E-day, was May 1, 1942. The family was given only ten days to pack up. “How can we clear out our house in only ten days?” her mother asked. “We’ve lived here for fifteen years!” For Mae’s family, the upcoming E-day meant shutting down their nursery business. What would they do with the greenhouses, delivery truck, and other equipment? For most Nikkei in this situation, the only answer was to sell, but with only a few days to unload their property, they were at a disadvantage. Families sold pianos for $25 or less. A twenty-six-room hotel sold for $500! The Oda family parted with a $1,200 tractor, three cars, three trucks, all their crops, and thirty acres of farmland for only $1,300. Mae Yanagi even had to leave behind her new bicycle, a gift for her seventh birthday.

At first the army carted Bay Area Nikkei to a temporary holding site, the Tanforan Assembly Center, in San Bruno, California. Detainees could bring only what they could carry. They received ID tags for themselves and their baggage. Each person was assigned a number, as was each family. The Yanagis were family 21578, and Mae was 21578G. The Uchidas were 13453; Yoshiko, 13453C. On their E-day, Mae and Yoshiko were loaded on buses and driven to Tanforan. Mae wouldn’t see the Bay Area again for three years, and she would never return to her home in Hayward.

Tanforan was a horse-racing track that the army hastily converted into a temporary detention center. Mae’s family was assigned to a horse stall, where they lived for four and a half months while their permanent “home” in Utah was being built. Though linoleum had been laid over the rough floorboards, the place reeked of horse manure, and it was furnished only with army cots. Yoshiko found herself in a similar stall, a rude replacement for her family’s sunny bungalow with its indoor plumbing and modern kitchen. After a brief time in Tanforan, a young child was heard to say, “Mommy, let’s go back to America.”

Copyright © 2020 by Michael O. Tunnell (Author). All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.