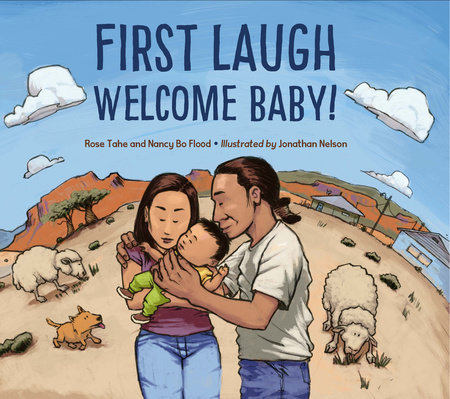

In Navajo families, a baby’s first laugh is more than a developmental milestone—it’s an honor to be the first person who makes the baby laugh, and the event is commemorated with a joyous gathering called the First Laugh Ceremony. The baby in this story, however, is making the family work for his giggles. “Your mouth open wide... It stretches... A smile? Oh, no. It’s a sleepy pink yawn,” write Tahe (a Navajo educator who died in 2015) and Flood (Cowboy Up! Ride the Navajo Rodeo). Not even baby’s ninaai (big brother), with his silly faces, can coax a grin. Then one day, cheii (grandfather) holds the baby high in the air, nima-sani (grandmother) whispers a traditional prayer, and “like babies everywhere—long ago and today—you laugh!” Debut illustrator Nelson, also of Navajo descent, contributes cartooning that captures an expansive, brilliantly hued outdoors and a close-knit family delighted with their newest addition. An extensive afterword gives more information on the ceremony as well as on baby celebrations in other cultures.

—Publisher's Weekly

In a "skyscraper home in the big, busy city" and amid the high desert mesas of the "Navajo Nation," family members attempt to make Baby laugh for the first time. Published posthumously with co-author Flood, Tahe's (Diné) debut picture book begins with four family members "watching, tickling, smiling [at]" a sleeping baby, wondering when they will hear the first laugh. Though the text itself lacks cultural identification in the first few pages, debut illustrator Nelson's (Diné) illustration supplies it, as two characters wear stylized hair buns on the nape to suggest a Navajo family. Before shifting to a rural setting on the Navajo Nation five pages later, the story continues in an urban environment with Grandmother tucking Baby in for a nap. For readers acquainted with Navajo culture, textual details such as "Pendleton blanket" and Nelson's visual cues, including Grandmother's turquoise pendant and a woven rug hanging on the wall, provide familiar touchstones. The remainder of the story sees all family members doing what they can to make Baby laugh. In Navajo tradition, families celebrate a baby's first laugh. Though an expository endnote on this and other new-baby celebrations indicates, "The person who succeeds…has the honor of hosting the First Laugh Ceremony," readers never fully feel that build of anticipation. Readers who note contrived moments of exposition and the romantic Native nostalgia reminiscent of Flood's other works might feel duped by the reverse alphabetical authorial billing. For those familiar with Navajo traditions, Tahe's knowledge and Nelson's illustrations give enough of a Where's Waldo breath of cultural clues to balance the scale and justify the buy.

—Kirkus Reviews