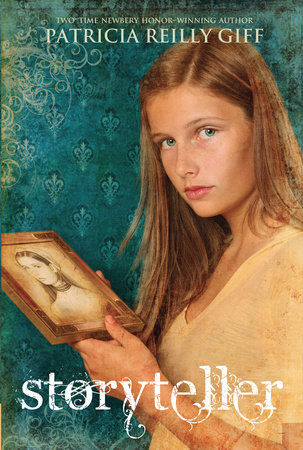

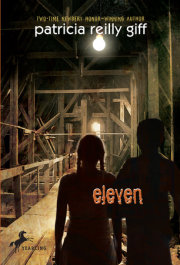

Elizabeth

Twenty-first Century

School's over; the weekend's here. Elizabeth heads for home. She'll put her feet up on the bench in the kitchen, read her library book, and finish off the brownies she and Pop made last night.

What could be better?

She trudges around to the back door, passing the living room, then Pop's workroom. She can see him through the window. He's long and lanky, his hair a little gray around the temples. He's leaning over his table, working on one of his carvings. On a shelf above his head, wooden animals march along in a row, and a face mask glares out at her. Weird. She tilts her head, picturing someone wearing that mask; a girl maybe, trying to look fierce. Her name would be . . .

Pop spots her. "Elizabeth?"

She climbs the steps, pushes open the door, and drops her backpack inside. "Hey, Pop," she calls.

"What were you doing out there?" he asks, coming into the kitchen.

"Just . . ." Embarrassed, she doesn't know what to say. "Just nothing, I guess."

She sees now that he has a line between his eyebrows.

Trouble. She tries to think about what she's done, or what she hasn't done. She grins to herself. Maybe it's something he hasn't done. The breakfast dishes are still in the sink; a plate with sandwich crusts is on the table.

"How about a hot chocolate to warm you up?" he says, taking the milk out of the refrigerator.

Still that frown. What's coming? She reaches into the cabinet for a couple of crackers.

"Listen, Elizabeth," he says. "I have to go to Australia. I've been asked to show my carvings at a university in Melbourne."

Australia! A million miles away. She blows air through her mouth. It means staying with Mrs. Eldridge and her fat bulldog with his horrible breath. But she can do that. She's done it dozens of times before when he's been away teaching or selling his carvings.

Pop runs a hand through his graying hair. "I called your aunt Libby. She says you can stay with her." He reaches for the box of cocoa. "She's only two or three hours away."

Elizabeth stares at him, a saltine halfway to her mouth. Her mother's sister? Elizabeth has seen her maybe twice in her life. Libby, a scientist, who probably spends her days in a dusty laboratory, working with little dishes of who knows what. She sends odd Christmas and birthday cards, her writing so small you can hardly make it out, and she doesn't have kids. Of course she doesn't.

"Libby!" Elizabeth explodes. "I don't even know what she looks like. I'll stay with Mrs. Eldridge."

Pop turns away to stir the milk on the stove. "Mrs. Eldridge is moving away."

"Alexa, then--she's my best friend, after all."

He pours the milk into a glass. It's so hot the glass cracks. Elizabeth watches the milk sizzle out across the stove, and thinks about her mother, who died in a car accident so long ago she can't even remember her.

Pop stands in front of her. "I might be gone several weeks, Elizabeth. It can't be helped. I wish it could. I don't want to go without you. I don't want to leave you for so long."

He hesitates, a dishcloth in his hands. "But it's time for you to know your mother's family. I've been feeling that for a while. Libby spent a lot of the last few years doing research in Canada, otherwise I'd have asked her sooner."

Elizabeth doesn't answer. She goes inside to turn on the television, pressing up the volume until everything around her vibrates.

Pop comes to the door. "I'm sorry, Elizabeth. I'm so sorry. This will be important to us, really. It'll mean more money, commissions for more carvings."

She turns away from him. Libby. A different school. She'll miss chorus and gymnastics. He's not worried about her missing school. One time she missed a few weeks. "You'll catch up," he'd said, knowing she would.

It's so unfair, but she knows there's no hope of changing his mind. Not by banging her bedroom door shut all week, not by skipping breakfast, not by saying she's sick and can't go to school.

The next Friday Pop brings two duffel bags from the basement. She stuffs almost everything she owns into them while he straightens the house and locks everything up.

They drive through a spring snow. It coats the windows like feathers; the windshield wipers drum back and forth.

"If this works out, I'll go back to Australia next year," Pop says. "Maybe you can go with me someday when we have more money. This trip I'll be able to sell some of the old carvings, things I did years ago."

"I don't care," she whispers, and wonders if he hears her. He turns on some horrible music, and she leans forward to switch to something else, something equally horrible.

"I love you, Elizabeth," he says.

She hums along to the music all the way, as if she can't hear him.

At last they stop at a house that's set back in a snowy garden. Elizabeth hunches her shoulders against the cold, against Pop, as Libby opens the door. She's tall, thin as a bone, peering at them with sky blue eyes behind her glasses. She's smiling, a tight smile, but still--

Good for Libby, Elizabeth thinks. She's not going to let us know what a horrible imposition this is.

Imposition. A word her English teacher, Mrs. Thomas, would love. Elizabeth feels a zing of pain in her chest. On Monday she'll go to a new school where she doesn't know a soul.

They drag her duffel bags through Libby's perfect hall, into her neat living room, and Pop leans forward to kiss Elizabeth good-bye, aiming for her cheek. She pulls back and he grazes her hair.

He mumbles a few words, and then he's gone.

Blotches of red stain Libby's neck. She moves forward and reaches out to Elizabeth. A hug? But Elizabeth realizes it's her jacket Libby's after. Drops of snow are beginning to melt on the carpet.

Elizabeth has to feel sorry for Libby. She imagines Pop calling on the phone, talking Libby into taking Elizabeth, as if she's the third duffel bag.

There's another sharp zing in Elizabeth's chest. Maybe something's wrong with her heart. She catches a glimpse of herself in the mirror. Nothing's wrong with her heart, of course. Too bad. It would serve Pop right if she keeled over and stopped breathing.

Copyright © 2011 by Patricia Reilly Giff. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.