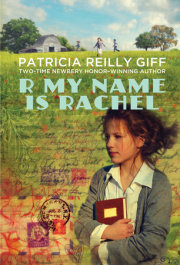

Chapter 1

“I’ll be right there, Rob,” I called.

Did my brother hear me?

He was in the kitchen chopping onions, the knife going a mile a minute. WJZ Radio was blasting news to anyone who wanted to listen. It was all about the war in the Pacific. I didn’t want to think about it.

I clumped into his boots. They were huge and much too heavy, but who knew where mine were? From my window, I’d seen a flower in the swampy pond at the end of our garden, a buttery yellow lily.

Amazing. It was late for flowers, almost winter. It might be close enough to pick. I was going to find out.

I took the path out back, stamped through the weeds, then stepped into the water, sliding a little. Mud and old leaves oozed up around my feet. From the corner of my eye, I saw something floating around on the other side of the pond.

My hat?

My old Sunday hat, the blue ribbons trailing behind, completely bedraggled!

How did it get there?

I couldn’t be bothered about that right now. It was the flower I was after.

I sloshed in a little farther. The water was freezing; I could feel it right through Rob’s boots. Then the mud covered the boots. I couldn’t take another step.

It reminded me of something I’d seen in the movies: a girl sinking to her nose in quicksand. “Arghh,” I whispered, just the way she had.

One day I’d be a movie star. I’d be grown up, and the war would be over. Or I’d be a famous chef, wearing a tall white hat, with movie stars crowding into my restaurant.

“Hey, Rob!” I yelled toward the house. “I’m stuck in here.”

He waved from the kitchen window, the chopping knife raised in his hand. “On my way, Jayna,” he yelled back.

I waited, paddling my hands in the icy water, wiggling my toes in his boots. The pond was filling in with old leaves and branches; the stream that fed it was no more than a trickle. Rob had said it wouldn’t be a pond much longer, just a patch of mud.

A couple of insects skated across the water and a blue heron high-stepped around the reeds. The turtle we called Theresa was in the middle of the pond, teetering on a thin branch that had broken off from the willow tree. Her shell was thick and curved, a beautiful brown and gold.

What would she do when her pond turned into a patch of mud? She’d have to take her dinner-plate-sized self and lumber off to find a new place.

What about me, when Rob left next week? He wouldn’t be coming home from the naval base every night. He’d be halfway around the world on a destroyer, fighting in the war I didn’t want to think about.

Theresa blinked with heavy lids. Maybe she was wondering about me, a skinny creature who fed her dried bugs and raw hamburger meat every day, a creature with sudden tears in her eyes.

I brushed at my face with two muddy fingers. Think about being a movie star. Rich and famous. Think about that tall chef’s hat plunked over my ginger hair.

Rob came across the yard and swung me out of the brackish water, leaving one boot stuck in the muck. My brother, Rob, nine years older than me, was big and bulky because he loved to cook and, even more, to eat anything he cooked! He was great at it: burgers and fries, steak and baked potatoes, lemon meringue pie and apple turnovers.

No wonder he was a cook in the navy. And now he’d be on a destroyer, the Muldoon, cooking for the sailors.

Do not waste one minute thinking about the Muldoon. Not even one second.

Rob looked at my muddy self. “So why were you trying to take a bath in the pond?”

I pointed to the yellow flower.

“You’d never reach that flower in a million years.”

“It was almost my last chance,” I said. “When you leave, I’ll be halfway across town, staying with Celine.”

Another thing not to think about! Celine, our landlady, would drive me out of my mind.

“Bad enough we have to have dinner with her every other minute,” I told Rob. “Worse that she’ll take care of me full-time.” He opened his mouth to say something, but I rushed on. “Don’t even say her name. I don’t want to think about Celine tapping around on Cuban heels, her hairpiece looped over one eye, telling me to act like a lady.”

“Poor Celine.” Rob leaned back against the scrawny willow tree. “Actually, she’s been a good friend and a good landlady.”

I wanted to say, Don’t go. I wanted to throw my arms around him and say, We just made ourselves into a family a year ago.

Not much of a family, only two people, but still so much better than before. I closed my eyes, remembering the day he’d come for me.

“Why don’t you wait?” Mrs. Alman, the foster woman, had said.

“Not even a second.” Rob had smiled at both of us. “No more Sunday visits. I’m old enough now, legal.”

I’d run down the path with him, looking back for a second to wave goodbye to Mrs. Alman, and in the car, the two of us had laughed with tears in our eyes.

“If only you didn’t have to go,” I said now. “Suppose you get killed?”

He shook his head. “Wait a minute, Gingersnap.”

My mother’s nickname for me.

Before I knew it, he’d sloshed into the water that didn’t even reach his knees and took three enormous steps toward the flower. He reached out with one hand, almost touching it.

I held my breath as the flower bobbed just out of reach.

“Yeow.” He slid into the mud, water spraying onto the bank, then came up, holding a stone in his raised hand. “No flower today, but this is for you, the world’s best soup maker. Now you can make stone soup.”

I grinned. I could do anything with a pot of vegetables, a little stock, a chunk or two of meat, and a pinch of basil or oregano.

The stone just fit in my hand. As I looked down at it, I could imagine a face: indentations that were almost eyes, a small curved nose.

“With that little turned-up nose, it almost looks like you,” Rob said.

“A funny face,” I said.

“That’s what makes it great. Imagine, it’s been around forever, rolling down from a mountain or coming up from under the sea. She might bring us luck, Jayna, this funny stone girl.”

“We need luck.” I slipped the stone into my pocket, and we went up to the house. I hopped, holding my bare foot up in the cold air. I held the sleeve of his wet jacket with two wet fingers.

“That water is really freezing,” he said, then stopped, frowning. “I forgot. Celine is coming to dinner.”

“I should have drowned myself,” I said.

“Instead of my boot.”

“You wasted a perfectly good night inviting her,” I said. “Lux Theater is on the radio at nine o’clock. I was going to curl up and listen. . . .”

“And I ruined a perfectly good jacket trying to get that flower for you. But maybe Celine will be gone by nine. Besides, I’ve made a perfectly good dinner. And afterward, we’ll get everything settled with her.”

That Celine.

I didn’t stop in the kitchen. I went down the hall toward the bathroom to sit on the edge of the tub, washing off my foot, thinking what it would be like here in North River without Rob. I was used to him coming home from the base every night and being free most weekends. That was why we’d chosen to live in North River, after all—to be together while he trained. I was used to cooking with him, laughing with him, hiking up the hills outside town with him.

When would the war ever be over?

Chapter 2

I went into the kitchen and set the table for the three of us, giving Celine the plate with the chip on the edge.

Rob thickened the gravy, stirring in cornstarch with rosemary and garlic, while I made lemon icing, eating a spoonful as I spread it over the graham-cracker cake he’d made.

He glanced across at me. “The cake won’t be as good as usual. Only one egg, and lard. It’s all because of the war. . . .”

He didn’t have to finish. Food was rationed, and we couldn’t always get eggs or butter. How hard it was to find everything we needed. Still, the dinner was going to be fine, just as Rob had promised.

News came from the small white radio on the shelf, hints of convoys moving toward the islands off Japan. That was why Rob was leaving the base and heading to California, where he’d board the Muldoon.

He saw my worried face. “She’s a great ship. Fast and sure in the water.”

I held up my hand. “Don’t.”

He nodded and started our game: what we’d do when the war was over and he came home.

When, I told myself. Not if.

“We’ll pack our bags and leave North River,” he began.

“Bringing all your recipe books,” I said.

He nodded. “We’ll go to Brooklyn.”

I didn’t know Brooklyn. I knew only those towns near North River where I’d lived in foster homes before Rob rescued me.

“We’ll open a restaurant,” I said. “You can cook all day.”

“And you’ll make soup.”

Celine knocked at the door and pattered in, her small feet on a pillow body, her hairpiece askew. What was underneath that nest?

She looked around as always, trying to see how we kept the house.

A mess.

We went to the table and Rob brought in the steaming dishes. Never mind the dust and the piles of books and sweaters on the couch; there wasn’t one thing wrong with the cooking.

Without thinking, I rested my arms on the table.

“Your elbows will turn into camels’ heels if you keep leaning on them like that,” Celine said.

I opened my mouth to say something mean, but Rob winked at me, so I closed it.

Celine knew it. “Closed teeth are fences against bad words.” She glanced up at the ceiling, her mouth filled with lamb. Her hairpiece slid lower as she chewed. How could she see?

She started in on the news, the war, and Rob’s leaving. “Dangerous,” she said.

As if we didn’t know it. Rob and I looked at each other, and suddenly it was hard not to laugh. Quickly I bent my head over my plate.

Celine hadn’t noticed. “But don’t worry,” she went on. “Think of that pilot, Eddie Rickenbacker, and his crew, who were on rafts in the Pacific for weeks, starving.” She shook her head, her hairpiece quivering, as she helped herself to half the bowl of carrots.

“A seagull landed on his hat,” Rob said calmly. “It was enough food to get them through.”

“Our fleet is massing for a huge attack in the Pacific,” Celine said, her mouth full. “Everyone knows that.”

Take a few deep breaths.

“So I’ll keep Jayna,” she went on. “I certainly will. I’m not doing it for money. It’s for the good of the country.”

“I’ll send you almost everything I make,” Rob said.

Celine was coughing now, choking on the pound of carrots she’d crowded into her mouth.

Some manners.

Rob poured a glass of water for her. In science class this morning, Mrs. Murtha had said, “Let’s think about water. If you drop a ball into a bowl, the water has to move away to make room for it.”

“Huh,” Joseph had said in his seat behind me.

Mrs. Murtha had ignored him. “When a ship enters the ocean, the same thing happens. The water has to make room for it. That’s called displacement.”

“Everyone’s displaced because of the war,” a voice whispered behind me.

Joseph? Diane?

No.

The whisper came again. “Pushed away from my misty silver lake, peace gone. I’ll have to spend my days here.”

I turned around. I saw . . .

Something? Someone? A lock of ginger hair, almost like mine, that faded into nothing.

Mrs. Murtha was staring at me.

Had I fallen asleep?

Now I glanced across the dinner table at Rob.

He was going to be displaced, taken away from North River, away from me. I’d be displaced into Celine’s house up on the hill.

I stared at my plate for the rest of the meal. I barely finished the lamb and hardly tasted the graham-cracker cake with the icing I loved.

At last Celine put on her hat. “I have to be home before it gets really dark. Who knows? Robbers and thieves may be hiding. . . .” Her voice trailed off as she opened our front door.

We watched her hurry down the street. “As if a robber would dare go near her,” Rob said, laughter in his voice.

We went back into the kitchen to cut ourselves huge slices of cake. Celine was gone! We could eat in peace.

Rob began to talk about the war. “My ship will steam into the South Pacific,” he said. “It will be part of a huge convoy to take the islands from the Japanese: Iwo Jima, Okinawa, then Honshu, Hokkaido. . . .”

Names that sounded strange to my ears. Names I didn’t want to hear.

The big radio was on in the living room and Lux Theater was beginning. “Don’t spoil the cake. Don’t spoil Lux.” I hesitated. “Suppose your ship is blown up.”

“You sound like Celine with her robbers and thieves.” He held up his hand. “The Muldoon’s a powerful ship. She cuts through the water like the blade of a knife.”

“What will happen to me if . . .” I couldn’t finish.

He came around to my side of the table and put his large hands on my shoulders. “You are tough, Jayna. You are strong. I’ve seen that over and over. You’re like our mother. You’ll always know what to do.”

Not true, I wanted to say. Not at all true. But still, how wonderful it was to be compared to the mother I never knew.

“So think that,” Rob said. “Jayna the strong. Jayna the brave.”

“Yes, think that,” a voice whispered.

I turned, but no one was there.

Copyright © 2013 by Patricia Reilly Giff. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.