How to Be the Lazy One

It’s harder than you think.

First, lie on your messy bed wearing your Wonder Woman pajamas that are too small because you’ve had them since you were nine. Then, watch your older sister, Leah, pin up her hair for dance class. She sits in her black leotard at the small white vanity, her back straight as a board, a magazine cutout of Paul Newman taped to the corner of her mirror. She uses at least fifteen bobby pins for her bun. Count in your head while she sticks the pins in.

One, two, three. She’s rushing because she has to be on the #4 bus by 9:00 a.m. for pointe class at Madame Duchon’s Dance Academy. She dances there every day except Sunday. You’re not even sure how she spends so much time at dance and still does well in school.

Leah seems to do well at everything.

Not you. You’re the lazy one. You’re just trying to keep up, but along with all the other things Leah does, she helps you keep up.

Four, five, six.

Ma wishes Leah didn’t take dance on Saturdays because of Shabbos, but Leah says it makes no sense for her not to dance if Ma and Daddy work all day at Gertie’s, their bakery. Then Ma says Leah’s right and that maybe they should be more observant and not work on Saturdays. Daddy says the bakery wouldn’t survive if they closed on Saturday in this town and that’s more important. They argue about the rules like that sometimes, how Jewish you’re all supposed to be.

Seven, eight, nine.

On pin ten, Leah suddenly stops and puts her hands over her face. Her shoulders start to shake. You lean forward in your bed, confused, to get a closer look.

Leah hardly ever cries. You’re the crier. It’s the only way anyone pays attention to you. You cry when you’re sad, or mad, or when you watch Lassie. Sometimes you even cry when you’re extra happy. You get it from Daddy. He’s a crier, too.

Leah manages to keep a smile on her face most of the time. If she’s upset, she gets serious and walks away, her shoulders straight, her head held high.

But today, on a warm Saturday in early June, as the sun tumbles through the window and the birds chirp and the smell of Ma’s Sanka floats in through the bottom of the bedroom door, Leah sobs into her hands, and it terrifies you.

“Leah,” you say, jumping out of bed and over to her side. “Don’t cry. What’s the trouble?”

She turns to you. She picks up a tissue off the vanity, presses it to her eyes, then blows her nose. “If I tell you a secret, will you promise to keep it forever?” she says.

“Forever?”

“Yes, forever,” she says. “It’s the biggest secret I’ve ever had, and if you don’t think you can promise, I won’t say it.”

Keeping a secret is not your favorite thing to do. Secrets make your stomach hurt. You can count on one hand the secrets you’ve kept. You once took a report card out of the mailbox and hid it in your schoolbag for a week. But you got caught. Sometimes when you hang out with your friend Jane, you make it seem like you have other friends. But you don’t. Occasionally you steal cookies from Gertie’s and keep them in a coffee can in your room. You’ve never had to keep a really big secret before, and certainly not forever.

Leah’s cheeks get blotchy, and her eyes start to fill again with tears. “Oh please,” she says. “I have to tell someone, and I need it to be you.”

Leah saying she needs you—is there anything more special than that? Maybe if you know her secret, some of her specialness will spill over onto you. She bites her lip and grabs your hand.

“Okay,” you say, taking a deep breath. “I promise.”

She holds up her pinkie and wraps it around yours. “Oh, Ari, something crazy has happened.”

“What? What’s happened?” A flush of sweat starts collecting on your top lip.

“I’ve fallen in love,” she says, your pinkies still linked together, her eyes still locked on yours. You let go of her pinkie and take your hand away.

“You’ve fallen in love? How? With who?” you say.

She gets up and starts to pace a little, so you sit down on your bed. You want to give her room.

“I’ve never felt this way about anyone. It’s like I can see my future,” she says.

She looks scared when she tells you this, and it makes you feel a little scared. You haven’t known anyone in love before. You’ve watched the soap opera Days of Our Lives with Ma, and it doesn’t look like much fun. It seems that people start having lots of problems when they fall in love.

If you think about it, you’ve been noticing some odd things about Leah, like the way she hums a tune everywhere she goes, even when Ma makes her clean the bathroom on Sundays. She wears her best clothes every day. She leaves a trail of Chanel No. 5 behind her, and she never used to wear perfume. She always seems to be thinking of something else.

“Who is he? Do I know him?” you ask her.

As she walks back and forth, she tells you that the boy she’s in love with is not a boy at all. He’s a young man about to graduate from college. He already enrolled in graduate school this fall because he wants to keep studying and doesn’t want to get drafted into the Vietnam War. She met him six months ago at Rocky’s Records in town. He’s from India, but he lives here now and works at Rocky’s after his classes because he loves music.

And he wants to marry Leah.

“Married? Now? You can’t be serious,” you say as your heart pounds in your ears. You don’t know what any of this means, and you don’t want anyone to take Leah away from you. How would she have any time to be your sister if she got married? It makes you want to give her secret back.

“I’m eighteen. Ma got married at eighteen,” she says, her eyebrows turning angry. “Lots of girls get married at eighteen.” She presses her hands to her cheeks as if she’s trying to hold herself in.

“I suppose so,” you say, still thinking she’s lost her mind. But it’s true. You think of Betty Campbell and Donna Marino, two girls who got married right after high school. They had their pictures in the local paper, and they looked like the plastic dolls Daddy keeps at the bakery to put on top of wedding cakes.

You remember feeling a little sorry for them, just going straight to the boring grown-up world with no in-between. You thought Leah wanted an in-between.

“When are you going to tell Ma? And Daddy?” you ask her.

Leah shakes her head. “Honestly, I can’t even imagine it. I need more time. Remember, you can’t utter a word. But this isn’t just some silly crush on a boy. This is serious.”

“You’ll have to tell them eventually,” you say. Leah doesn’t reply. “Are you really going to get married? To a boy from India? Is he Jewish?”

“He’s not a boy,” Leah says loudly, and anger washes over her face. She takes a deep breath. “And of course he’s not Jewish.”

“Well, I don’t know.”

“He’s Hindu,” she continues in a smaller voice. “I’m worried about what people will think if we get married.”

You nod slowly. Leah is the one who’s supposed to follow the rules. It’s no secret Ma and Daddy want her to go to college and marry someone Jewish. She already enrolled at Southern Connecticut State for the fall, though if it’s anything like your town, there won’t be many Jewish boys there.

Leah sits back down at the vanity.

“But I’m also worried about what will happen if we don’t. I really love him,” she says and starts to dab her face with her pink powder puff, erasing the streaks her tears left on her cheeks. “Sorry, I don’t mean to be a drag.”

“It’s okay,” you say and go over to her. You put a hand on her shoulder. “You’ll figure it out.” But what you really mean is that she’ll figure out that she’s not in love or thinking about marrying anyone.

How to Keep a Secret

About a week later, neither of you is worried anymore, because it’s almost summer vacation and it feels like you’re in a movie—Leah’s movie—and your beautiful, smart, talented older sister trusts you with her secret love story.

You’ve never been close to being in love, and that’s just fine. Yes, you’re only eleven, and all the boys you know are kind of mean or smelly or both. You can’t imagine ever feeling that way about any one of them. Who would ever love you like that? You aren’t that pretty. You aren’t that smart. You certainly don’t feel smart at school, especially when you write.

Writing is to you what dancing is to the clumsiest person in the world. Daddy says your hands need to get stronger, not your brain. But you think he’s wrong. You think it’s your brain. You heard your tutor last year telling Ma that she thought you had something called a learning disability. Ma sent that tutor away.

Still, Ma makes you knead bread dough to make your hands stronger. You like helping at Gertie’s. There, your hands work the way they’re supposed to. It hasn’t made your writing any better, though. Ma calls it chicken scratch. It’s not just hard to write, it’s hard to think of what to write. Sometimes you can’t even read your own writing. It’s like a secret code.

As you walk into the bakery, you feel the afternoon heat surround you like a heavy cloud. It’s hot outside and even hotter in the bakery. You don’t know how your parents do it.

In the afternoons, you usually help Ma with cookie dough, and then Ma walks home with you at five to get dinner going, but Daddy’s in the bakery from four in the morning until seven at night, except on Mondays, when the bakery is closed. Daddy has the strongest hands of anyone you’ve ever known, and his handwriting is beautiful. He writes the daily special on the chalkboard every day in perfect curly cursive.

Daddy stands across the room, forming bread dough into loaves. You can tell from the brown caraway seeds that look like ants in the mass of sticky white that it’s rye. Daddy’s hair is plastered on his forehead, and he moves slowly in the heat. He looks up.

“Have any homework, Muffin?” he says.

“Already did it,” you reply, which is almost true, except for the questions you had to answer about your reading. You did your math, though.

Ma and Daddy always let you have a little break before they put you to work, so you grab a cold cola from the fridge and collapse on the stool near the pastry table. Just touching the cold glass of the cola bottle makes you feel better.

After a few minutes, Ma comes over. “Why are you always reading those ridiculous comic books?” she says to you as you flip through the latest Wonder Woman while sipping your soda.

You want to say to her that you don’t read ridiculous comics. You read Wonder Woman. You’ve tried Superman, The Flash, even Aquaman, but nothing is as good. Something about the pictures helping the words go together in small chunks feels like the puzzle piece your mind is missing. If only all schoolbooks could be like comic books.

Before you figure out your answer, Leah comes bounding through the swinging doors. She often stops by after dance on her way home. Ma doesn’t make her help as much as you. She says it’s because Leah’s older and busier, but you think it’s because Ma doesn’t want Leah to get used to working at the bakery. She wants her to do other things.

Usually, Leah’s still in her dance clothes, but today she’s in a red-and-white miniskirt, and her hair is down. She must have gone home first and changed.

“Ma, how can you stand it in here? Let’s turn on the fan. We’ll all melt,” she says, waving her hand in front of her face. She goes over and turns on the big fan in the back and opens the door a few inches.

“Well, look at you,” Ma says and runs her eyes carefully over Leah. “A secret date?”

Leah doesn’t miss a beat. “A secret date, I wish,” she laughs, then changes the subject. “Ari, want to walk with me to the Sweet Scoop?”

You nod and quickly close your comic book. The last place you want to be on this sweltering afternoon is the bakery.

“Can I?” you say, turning to Ma.

She eyes you carefully and then looks at Leah again. Does Ma know what Leah’s up to? She’s always telling you she has eyes in the back of her head. When you were little, you used to move her hair aside, looking for those eyes. Also, your sister is a great liar, which makes you wonder if she’s ever lied to you.

“But I need you to help me with an order of oatmeal raisin,” she finally says.

“Ma, give Ari a break,” says Leah. “It’s so hot.”

You don’t like making oatmeal raisin cookies. The batter is lumpy. You also hate raisins. You prefer making chocolate chip or black and whites.

“Let her go, Sylvia,” Daddy calls. “She’s here almost every day.” He’s the softy.

“Fine, go,” she says, waving her hand without looking up. You and Leah don’t wait for her to change her mind, and rush out the door.

Leah has been bringing you with her to meet Raj at Rocky’s and go on his break with him. That way it will look less suspicious. This is the third time you’ve gone with her.

The three of you have a routine. You get Raj at Rocky’s and then go to the Sweet Scoop. After you order your ice creams, you all walk through Stallings Park, the smaller park on the edge of town that is loud and filled with young people sitting on blankets, playing music on their transistor radios, and sometimes smoking cigarettes. Ma told you and Leah if she ever catches you smoking, she’ll never let you go anywhere without her again, even though Ma sometimes smokes a cigarette after dinner.

At first you were nervous and decided that you wouldn’t like him at all. But Raj was so nice to you, you couldn’t help liking him. He kind of looks like Elvis, but with darker skin, and always buys you a double fudge ripple cone. It doesn’t feel like anyone is taking Leah away from you. In fact, you get to be more a part of her life than ever.

Today, as the three of you walk through the park, Leah says, “Can you believe Ma used to bring me here when I was little? Now the families go to East Meadow.” East Meadow Park on the other side of town is bigger and quieter, with more flowers and no teenagers. Occasionally, a grown-up, usually a man in a suit carrying a briefcase, cuts through Stallings to get to the train station and squints his disapproval at a blaring radio.

“I always went to East Meadow when I was a kid,” you say.

Leah looks at you and laughs. She rumples your curls. “You’re still a kid.”

You frown at her and duck away from her hand. You want to stick your tongue out at her, but then she’d be right.

“I’m almost twelve, which is practically thirteen. I’m basically a teenager, just like you.”

“First of all, you’ve got a while before twelve,” Leah says. “And second, I’m seven years older than you. Don’t be in a rush, Ari. Nothing’s wrong with being a kid.” Her eyes travel away from you and back to the park. Her mouth falls out of its smile, and she suddenly looks sad. Then why are you rushing, you want to ask her.

“I like it here,” Raj says, slicing through whatever Leah is feeling. “It reminds me of a park near my flat in Bombay. My cousins and I would play cricket there.”

Leah takes Raj’s arm, her eyes sparkling. “Tell me more about your family. I want to know everything about you.”

You roll your eyes, walk a little bit ahead of them, and plop down on a bench. You lick your melting cone and wonder what kind of game cricket is. Does it involve actual crickets? You want to ask, but it seems like a question a little kid would ask.

“We’re going to take a walk, okay?” Leah calls out. This is also part of the routine. They usually leave you on a bench for a little while to eat your fudge ripple while they wander behind a cluster of oak trees. A few days ago, you saw them feed ice cream to each other and kiss. You turned away, your cheeks on fire. Now you know why they go behind the oak trees. A part of you wants to spy on them, and a part of you wants to run far, far away.

After a little while, the three of you stroll back to the store, but they don’t hold hands in case they run into anyone they know. You like listening to their conversations. They discuss all sorts of things. They talk about music a lot: the Beatles, the Doors, Jimi Hendrix, the Rolling Stones, Aretha Franklin. They argue about which band is their favorite. Raj likes the Doors the most. Leah thinks the Beatles are groovier.

They talk about serious things, too, like the war in Vietnam, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s speech in New York City that spring against the war, and the protest marches for civil rights and peace that they want to be part of. Today they talk about the uprisings happening around the country, and you wonder what they mean. Leah says she understands why Black people are so upset. Raj says riots aren’t the way to change things, that nonviolent protests are more powerful, like what Gandhi did in India, like what Dr. King is doing now.

“But don’t you think that the Black community has no choice but to fight back and defend themselves against hundreds of years of racism and violence? What if peaceful protests aren’t enough to change things? Have you read Malcolm X’s autobiography? And look at what the Black Panthers are trying to do,” Leah says. “It must take so much courage.” Leah crosses her arms. You’ve never seen her speak this way to anyone. Other than Dr. King, you don’t know who she’s talking about.

“But how can we really understand, Leah?” Raj says.

“We have to do more. We’re both not part of the majority. How can we not understand?” she replies.

You watch Leah’s face, then Raj’s. Are they mad at each other? You can’t tell.

“I think I have a different perspective rather than a better understanding,” Raj says. “When I came here, I felt like the best thing to do as an immigrant was try as hard as I could to blend in so no one would notice the color of my skin. Does that make me a coward?”

Leah gets quiet. She shakes her head and reaches out to squeeze Raj’s hand quickly before letting go. You feel more confused than ever. You think about protests and riots and what they are for. You wonder what Raj means by blending in. You didn’t know Leah paid so much attention to the news.

You also learn more about Raj. You find out that he grew up in Bombay, a big city in India. That he has two much-older brothers, one still in India and one who lives here. You find out that his favorite flavor of ice cream is pistachio and that he loves pizza.

Another thing you find out is that Leah and Raj go out every Tuesday night to a pizza parlor two towns over so no one sees them. Ma thinks Leah is in her pointe class. You know lots of secrets now, which started off feeling special, but the feeling is getting heavier and heavier as each secret stacks upon the other. What Leah and Raj don’t talk about in front of you is their future.

After this trip to the park, back at Rocky’s, Raj gives Leah a present, the new Beatles’ album. She jumps up and down and throws her arms around him. Everyone in the store looks at them. You don’t like the way people stop and stare. You want to pull Leah away, but she doesn’t seem to notice.

Then Raj goes back to work, and Leah and you walk home.

“I know I promised to keep your secret,” you say after you get far enough away from the store. She faces you, clutching the Beatles’ album against her chest.

“Yes, you did,” she says, waggling her finger at you, a panicked expression on her face.

“I still promise,” you say. “But when are you going to tell Ma and Daddy?”

You read the title on the album: Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. You wonder what it means. Were the Beatles changing their name? Your hands feel sticky with ice cream. You press your thumb and forefinger together, and they stay stuck that way.

“I’m just so happy. I don’t want anything to ruin it. I feel guilty about being so happy.”

“Why would you feel guilty about being happy?” you ask.

“Because there’s so much wrong with the world,” she says and starts walking again.

There is, according to the newspapers. But you look around your town. You see someone driving by in a blue Chevy convertible. You see people walking down the block in sunglasses, sipping soda pop, riding their bikes, happy to be out on such a nice Saturday. This world seems okay.

“Do you know what happened at Rocky’s last week? A guy came in and heard Raj talking. Then he asked John, the manager, why he had foreigners working there and not Americans. He asked Raj if he was here legally. Raj said he was a US citizen, and the fellow demanded to see proof and wouldn’t leave! John had to threaten to call the cops until he finally left.”

“Gosh, that’s terrible,” you say. Now she’s walking so quickly, you can barely keep up.

“But our love is stronger than the racist establishment.”

“‘The racist establishment,’” you say, trying out her words. Lately, Leah says things that feel so grown-up and strange, like they belong in someone else’s mouth. Leah stops walking, so you stop. You can see her cheeks becoming red, her chest going up and down like she’s out of breath. The air is sticky and still.

“I’m not naïve, Ari. I see the looks people give us when we walk down the street. It’s not going to be easy for me and Raj.”

“So maybe you shouldn’t get married?” You’re starting to feel like you’re walking into a pool that’s getting too deep for your feet to touch the bottom. A worry for Raj and Leah, in a new way, a way you hadn’t even thought about before, is nagging at you. Other people won’t like them together, not just your parents. You shake your head. You’re ready for Leah’s secret love-story movie to end and to go back to just Ariel and Leah—the way it used to be.

“But then they would win,” she says.

“Who would win?” you ask, but Leah doesn’t seem to hear you.

“It’s not just what Raj faces. We know about prejudice,” Leah says.

“We do?” you ask, and again that feeling of the pool getting deeper takes hold of you. Now Leah is a few feet ahead. “Hey, slow down,” you call, because it’s too hot to walk this fast.

She stops and faces you again. “Of course. I once heard Ma and Daddy tell their friends how the bank wouldn’t give them a loan because they didn’t think a Jewish bakery would do well here. Daddy had to convince them that his baked goods were for everyone. He even brought them a box of cookies to prove it.”

“I didn’t know that,” you say, and it makes you wonder what else Leah knows that you don’t.

“And Ma and Daddy’s friends from synagogue, you know the Feldmans? They tried to sign up for that golf club in Milton, and they were told that membership was full, but then the Cunninghams joined a week after.”

“But that’s not fair,” you say, and it feels like Leah has ripped the cover off something ugly and confusing, something you don’t want to see.

“And remember what that awful boy did to you last year?”

“I don’t like to think about that,” you say and bite your lip. But you do think about it, a lot. You and Chris Heaton had both wanted the last empty swing. You got there first by a second, but Chris insisted he was first and told you to get up. You refused. Then he leaned in and touched your head.

“Where are your horns?” he asked.

“What?” you said, brushing his hand away.

“My dad told me Jews have horns,” he said and touched your head again. “Like the devil.”

“Get away,” you said and then touched your own head, wondering if there was something you had never noticed before.

He kept asking where your horns were, getting louder and louder. He wouldn’t stop. So you picked up a small rock and threw it at him, but it hit him in the face.

You had just wanted to stop him, not hit his face. He stared at you, frozen, holding his cheek. Then he ran off and told the playground monitor, acting like you had shot a cannonball at him. You got in more trouble than he did, detention for a week, and all he had to do was talk to the principal.

At home, Ma and Daddy had explained what the horn statement meant—how it had to do with a wrong translation in the Bible saying that Moses had horns instead of light around his head when he came down from Mount Sinai. Ma said it was still used as a slur today and that some people actually believed it was true. It felt like someone had slapped you when she told you this. How could anyone believe such a ridiculous thing, as if you were a different kind of person or maybe not even a person at all?

Ma had been furious and wanted to talk to the principal. “That boy should be suspended! We can’t let this go,” she had said. But you begged her not to; you were afraid it would only make Chris worse. Daddy agreed. “Let’s not make a fuss, Sylvia,” he had said. “We don’t need that kind of attention. Think of the bakery.”

Back then, you had wondered what kind of attention Daddy meant. Now you wonder what really changes people. You had tried stopping Chris with the rock, and it did stop him, but you don’t think it changed him. Should you just have let him take the swing? Should you have sat there silently, refusing to leave? You don’t know if that would have changed him, either. When you play it over in your mind, you never come up with a good answer.

Suddenly you hear someone calling you. You look up to see your friend Jane coming down the street with her mother. The two of them live on the floor below you. You ride the bus together to school.

“Why, hello, girls,” Jane’s mother, Peggy, says, taking off her big round sunglasses. “Where are you coming from?”

You and Leah glance at each other.

“The Sweet Scoop,” Leah says.

“That’s where we’re off to. If June is starting off like this, we’re probably in for a long, hot summer,” she says, fanning herself.

You both nod.

“Oh, oh, oh!” Jane shrieks, jumping up and down. Everyone looks startled.

“What on earth?” Peggy says, putting her hand to her chest.

Jane points at the Beatles’ album. “How did you get that? I thought Rocky’s was sold out. They said they weren’t getting more until next week.”

Leah looks down at her hands like she forgot what she was holding.

“Oh, this, well, I—”

“She put it on hold the day it came out,” you say. “But you can come over and listen if you want.”

You see Leah’s shoulders drop in relief.

“That would be far-out! Thanks! See you in school tomorrow, Ari,” Jane calls as she and Peggy head to the Sweet Scoop.

“That was clever of you,” Leah says after they walk off. “Imagine if we saw them with Raj . . . ”

“Yeah, Peggy would have definitely said something to Ma.” Peggy and Ma are sort of friends; at least they like to chat in the laundry room on Sundays, but Ma doesn’t seem to have time for many friends.

Leah’s face changes, and she gets that hard look with her eyebrows knitted together. “Eventually, someone is going to see us and tell Ma and Daddy. I want them hearing the truth from me first,” she says. “I’m just going to do it. I’m going to invite Raj over.”

“Oh good,” you say and give Leah a little hug. You aren’t sure how Ma and Daddy are going to react to Raj, but at least you won’t be the only one to know anymore. You both walk home, and your whole body feels lighter, like Leah just took something out of your hands and decided to hold it herself.

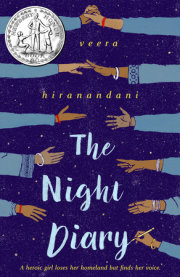

Copyright © 2021 by Veera Hiranandani. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.