What Do We Know About the Curse of King Tut’s Tomb?On November 26, 1922, Howard Carter walked down a long, dark corridor leading underground into the sands of the Egyptian desert. At the end was a door to a tomb that had been closed for over three thousand years.

The door was stamped with the name of an ancient Egyptian pharaoh (king), Tutankhamun (say: toot-an-KHA-moon).

Carter was an archaeologist, someone who studies ancient cultures by unearthing the objects created by them. He had been digging for years in his search for Tutankhamun’s tomb. At last, he had found it. His hands trembled as he held a candle up to the door.

Carter was not alone. Standing behind him was Englishman Lord Carnarvon and his daughter, Evelyn. Carnarvon was a wealthy aristocrat who had paid for Carter’s expedition and work to find the tomb. Like Carter, Carnarvon was fascinated by ancient Egypt. Now it seemed they were about to make a great discovery. Carter picked up an iron rod and poked a hole through the top left-hand corner of the plaster door. He put his candle through the hole to see what was inside. The hot, musty air that escaped made the candle flicker. Slowly, Carter’s eyes adjusted to the light and he could see strange shapes among the shadows. There were statues, furniture, and the glint of gold everywhere.

Carter stood still, dumbstruck. The treasures in the tomb were beyond his wildest imagination.

“Can you see anything?” Carnarvon asked anxiously. “Yes,” Carter finally managed to reply. “Wonderful things.”

It was an extraordinary moment. Although many archaeologists knew the name “Tutankhamun,” few believed his tomb would ever be discovered. No one expected it would be found with its treasures intact. Many pharaohs were laid to rest with a large amount of precious objects, and their tombs were often plundered by robbers, some soon after the pharaoh had been buried.

In ancient Egypt, entering the tomb of the pharaoh and stealing from it was a serious crime. Those who were caught would be executed. And it was believed that those who were not caught might be struck down by a curse. A pharaoh’s curse was like a spell, a punishment that was said to bring bad luck, illness, or even death. Specific curses were sometimes written near the entrance of a pharaoh’s tomb to warn intruders and thieves away.

Howard Carter had not seen a curse posted at Tutankhamun’s tomb. But nothing would stop him from entering even if he had. Discovering the tomb and all its contents was an archaeologist’s dream. Carter did not know it yet, but he had just made the largest discovery of Egyptian treasures in history. But perhaps he was also about to uncover something disturbing and frightening.

Because soon after discovering the tomb, strange things began to happen to those involved. These events led many to believe that the pharaoh himself was punishing those who had disturbed his resting place from beyond the grave. In finding the pharaoh’s tomb, had Carter also unleashed the curse of Tutankhamun on the world?

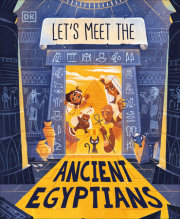

Chapter 1The Boy KingTutankhamun is often called “the boy king.” That’s because he was only eight years old when he became pharaoh, in 1333 BCE. Although he was young, Tutankhamun had inherited one of the most advanced civilizations of the ancient world.

Even at that time, Egyptians were already expert builders and engineers, highly skilled scientists and scholars, and accomplished artists and craftspeople. In addition to their pyramids, temples, and palaces, Egyptians had created a written language and complex religion, and made beautiful jewelry, sculptures, and wall paintings.

Egypt’s pharaoh was like a living god on Earth. Almost always male, the pharaoh was believed to be unbeatable on the battlefield and wore a crown with a uraeus (say: YOO-ree-uhs), a small cobra figure that could supposedly spit fire at his enemies. The cobra was also the symbol for the goddess Wadjet (say: WAAD-jet), one of the many gods the Egyptian people worshipped.

The Egyptian gods also included Amon-Re (say: AH-muhn-ray), the king of the gods, and Osiris (say: OH-sai-rus), the god of the afterlife. In Egyptian wall paintings, Osiris is often shown alongside Anubis (say: uh-NOO-bis), the god of mummification. The Egyptians believed that after death, a person would be judged by Anubis, who would then weigh the person’s heart against a feather to see if they were without sin. If the heart was as light as the feather, the person would be presented to Osiris and allowed to enter the afterlife. If the heart was heavier than the feather, it was gobbled up and the dead person would no longer exist.

Preparing for death was extremely important to the Egyptians. And the Egyptian pharaohs were buried with everything they would need in the afterlife: clothes, food, furniture, and personal possessions. A pharaoh’s tomb was filled with treasures and decorated with painted murals.

It often took years to prepare the tomb and the interior space. For example, Pharaoh Khufu began designing his tomb as soon as he inherited the throne, in around 2550 BCE. This took around twenty years to complete and it became one of the largest stone structures ever constructed: the Great Pyramid at Giza.

A pharaoh could not be disturbed after being buried in his tomb. Those who broke this rule were in danger of being cursed. Curses were written at the entrance of tombs, or sometimes inside the tomb on a stone tablet. One example read: “Cursed be those who disturb the rest of a Pharaoh. They that shall break the seal of this tomb shall meet death by disease that no doctor can diagnose.”

A curse on another tomb read: “All people who enter this tomb who will make evil against this tomb and destroy it: may the crocodile be against them in water, and snakes against them on land. May the hippopotamus be against them in water, the scorpion on land.” This meant the curse for entering and damaging the tomb would be attacks by crocodiles, snakes, hippopotamuses, and scorpions. The curse would find you wherever you were: on land or in the water.

Ancient Egypt Located in hot, dry North Africa, Egyptian culture began around 6000 BCE as groups of small farms along the Nile River. Every year, the Nile flooded the farmland, bringing rich soil and nutrients carried by the water onto the land. This made Egypt a fertile place with plenty of food. Over thousands of years, Egypt grew into a wealthy kingdom ruled over by powerful kings, called pharaohs. The pharaohs constructed cities, such as Thebes, Aswan, Luxor, and Memphis (near today’s capital, Cairo), and massive pyramids near Giza to be buried in. Later pharaohs built their tombs underground in the Valley of the Kings.These warnings were supposed to scare intruders and robbers away. But the Egyptians realized the curses were not enough to keep tombs safe. Hundreds of years later, it was decided to bury the pharaohs in underground tombs in a secret location. This location became known as the Valley of the Kings.

The Valley of the Kings is a dry, lifeless place located in the Theban Mountains. Here, temperatures can reach 120 degrees and there is a blinding glare from the dazzling white limestone rock. Normally there would be little reason to go to the Valley of the Kings. This is exactly why it was chosen to bury Egypt’s pharaohs, between 1539 and 1075 BCE. Unlike the Giza location, tombs in the Valley of the Kings were not marked by giant pyramids. The valley was a barren area where underground tombs could be concealed—a place where kings and queens could rest in peace for eternity. One such tomb would belong to Tutankhamun.

Unlike Pharaoh Khufu, Tutankhamun did not start planning his tomb right away. He was a young boy who depended on advisers to help him rule. As a young boy and teenager, Tutankhamun had a pleasurable life in luxurious palaces. Servants attended to his every need: bathing and dressing him and bringing him food. He spent time hunting in his chariot with a bow and arrows or taking boat trips down the Nile. He dressed in fine white cotton and jewelry made of gold and precious stones. He wanted for nothing.

However, Tutankhamun had inherited a troubled kingdom. His father had been the unpopular ruler Amenhotep (say: AH-muhn-how-tep) IV. Amenhotep had announced that Egypt would only worship one god, Aten the sun god, and closed most of the country’s temples. He then changed his name to Akhenaten (say: AH-kuh-naa-tin) and built a new capital city in the middle of the desert. Suddenly, all the other gods people had worshipped their whole lives were gone, and thousands of priests who had been dedicated to each specific god were unemployed. Akhenaten was so disliked that people destroyed his statues after he died.

Egyptians were relieved when the new pharaoh, Tutankhamun, restored the old religious system. He became a well-liked ruler who, at age ten, married his sister, the thirteen-year-old princess Ankhesenamun (say: ANK-KESS-in-imin). This was not considered unusual at the time. Marrying within the family helped ensure the line of succession, and the family would continue to rule without being challenged. The couple were fond of each other, but their marriage did not last. At eighteen years old, Tutankhamun died suddenly. Some think he was murdered, perhaps by a blow to the head by one of his own advisers. Few people had expected Tutankhamun’s death. His tomb had not yet been prepared. But his burial had to take place quickly so his journey to the afterlife could begin.

Before being buried, a pharaoh had to be mummified. This was a process of preserving the body. The organs such as the lungs, liver, and stomach were removed and placed in special jars. A hook was pushed into the nostrils and used to pull out the brain. The body was then covered in salt and stuffed with straw to dry it out. This was the ancient Egyptian style of embalming. After forty days, the stuffing was taken out and replaced with linen. Finally, Tutankhamun’s body was wrapped in strips of linen and placed in a coffin.

It was not only humans who were mummified in Egypt—animals were, too, including cats, birds, crocodiles, and even fish. Some pharaohs were buried with their mummified pets. However, the most care was given to the bodies of the pharaohs.

After mummification, Tutankhamun was carried to his tomb in the Valley of the Kings during a secret ceremony. No one besides those involved in the burial could know where his body was placed. As his servants and priests left the tomb, they sealed up the doors with plaster. Tutankhamun and his possessions would lie undisturbed for thousands of years.

Copyright © 2025 by Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.