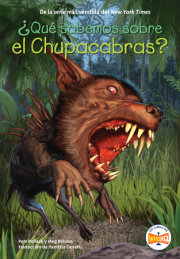

What Do We Know About the Chupacabra? On the morning of May 22, 1995, Don Francisco Ruiz walked outside his home in Humacao, on the eastern shore of Puerto Rico. Along with several beaches that draw a lot of tourists, Humacao boasts a large tropical forest and miles of flatland where people raise crops and animals.

Francisco was a rancher. When he went out to check on his animals that morning, his cattle were fine. But when he came to the enclosure where he kept his goats, he had a terrible shock. Three of his goats lay dead on the ground.

Francisco knelt down to examine them. Each one had what looked like puncture marks on its body. He thought an animal must have attacked them. But what kind of animal? He looked closer at the puncture wounds. Something had bitten his goats. But there was no blood on the ground or in the wounds. In fact, it looked as if the goats had been completely emptied of blood.

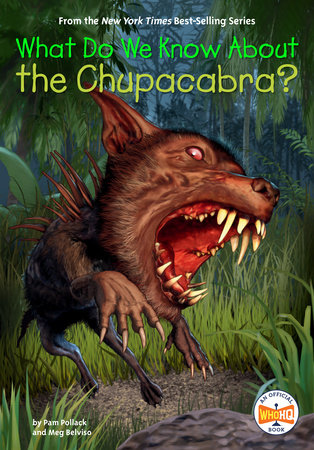

Don Francisco Ruiz knew a lot about animals. He was a farmer who knew what cattle ate and how goats behaved. But he likely did not fully understand what he was looking at. What had happened that night? What kind of animal would do this to his goats? Francisco’s own blood ran cold. He remembered reports in local newspapers and on the radio about farm animals with strange wounds, animals that had been found completely drained of their blood. Although no one had seen the creature that did this, its name was being whispered all over Puerto Rico. In Spanish they called it the Chupacabra, or “goat sucker.” Had this mysterious beast visited Francisco’s farm?

Chapter 1: Cryptids Today, anyone can look up information in books or on the internet about the animals in our world. We know why some eat plants while others eat meat. We understand why some have fur and some have scales, as well as where they live and how they travel. Even if you have never seen a penguin in real life, it is easy enough to find pictures or videos of them.

Long ago, this wasn’t the case. People had no idea what kinds of creatures might live out in the parts of the world they had never seen. They imagined things like the ichthyocentaur (say: ICK-thee-o-CEN-tor)—part human, part horse, part fish, and able to play musical instruments—and creatures such as mermaids. Many beings that we know are imaginary today were once thought to be real. Mapmakers even sometimes drew mythical beasts and animals on maps to show people where they might be found. To someone who had never seen an elephant, that massive creature might seem as fantastical as an imaginary unicorn.

Even today, we can’t be sure we’ve documented every animal that exists in the entire world. Cryptozoology (say: KRIP-toe-zoh-AHL-o-jee) is the study of mysterious creatures whose existence hasn’t yet been proven.

Crypto means hidden and

zoology is the study of animals. The animals that cryptozoologists search for are called cryptids because if they

do exist in the world, they remain hidden. We don’t yet have proof that they exist. Bigfoot, the hairy giant some say stalks the woods of North America, is a cryptid. So is Nessie, the underwater monster said to live in Loch Ness, a lake in Scotland. And so is the Chupacabra.

Cryptozoology is not considered a true science, because science studies things that can be observed. But many people still believe that reports about beings like Bigfoot should be taken seriously. After all, some animals that once seemed fantastic turned out to be very real.

The narwhal is a type of toothed whale that lives in the Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. Because of the large tusk growing out of its upper jaw, it’s nicknamed “the unicorn of the sea.” In the Middle Ages (a period of European history from the late 400s to the 1400s), narwhal tusks were sold as actual unicorn horns. Some people believed they had magical powers.

Narwhals are very real. Yet every month, almost fifteen thousand people search the internet to ask: “Are narwhals real?” So even the existence of real animals that we have studied and documented is sometimes questioned.

In order to know that an animal definitely exists, we need proof, like the body of a giant squid or a captured narwhal. Without an actual sighting of the animal, any small bit of evidence will do: a strand of hair, a footprint, a nest, or a piece of skin or scale. That is what cryptozoologists search for. In 1995 they began looking for a new cryptid in Puerto Rico: the Chupacabra.

Chapter 2: Making Headlines The town of Orocovis is located in the Central Mountain Range of Puerto Rico. The mountains cross the island from east to west, dividing it into northern and southern coastal plains. Because of its central location, Orocovis is sometimes called the Heart of Puerto Rico. Many people in the region make their living by growing wheat and coffee, or raising livestock like goats, sheep, and cattle.

In March 1995, several residents of Orocovis and the nearby town of Morovis woke up to discover their some of their livestock had been killed. Ranchers went to their fields and found goats, sheep, and cows lying dead with small puncture wounds in their necks. Even more chilling, the animals seemed to have been drained of blood. No one had seen any evidence of a person or animal that could have killed them. What was attacking their valuable livestock? By the time Don Francisco Ruiz found his own goats dead outside his home in Humacao, he had already heard about the attacks in Orocovis. Eventually the mysterious creature was given a name: Chupacabra, or “goat sucker.”

Giving the creature a name made it easier to talk about. At first, the stories were spread from person to person. People passed on rumors that they heard from a cousin about a neighbor whose sheep had been killed by a monster. But soon the stories caught the attention of local newspapers. The publishers of those papers knew they could sell a lot of copies with headlines about a monster stalking the countryside.

In 1995, the most popular newspaper in Puerto Rico was

El Vocero (say: el vo-CER-o), which means

The Spokesman. Today, the paper publishes many types of news, but back in 1995 it was known for its focus on dramatic stories, especially violent ones, which it advertised in big red headlines.

The Chupacabra quickly became the star of

El Vocero. The paper published story after story about the mysterious creature, often written by the same few writers. Reporter Ruben Dario Rodríguez alone was responsible for nearly half the Chupacabra articles the paper ran. The more stories Rodríguez wrote, the more exciting the details became. The reporters at

El Vocero didn’t spend much time trying to prove whether or not the stories were true. They just repeated what people told them.

For instance, in November 1995, the paper claimed the Chupacabra had killed a cat and a sheep before swallowing an entire lamb whole. No one actually saw the lamb being swallowed by anything. That was just the conclusion the journalists came to when the lamb couldn’t be found. A few days later the Chupacabra was reported to have killed five chickens before placing a strange mark on the arm of a five-year-old girl whose parents owned the chickens. The experience was said to have turned the girl into a genius! There were no follow-up stories proving that the girl was now brilliant, and no one examined the mysterious sign on her arm. They just moved on to the next story.

Whether or not people believed any or all of these stories, they definitely popularized the mysterious creature and sold newspapers. But if the Chupacabra was a real animal, some people wondered why it only started being widely reported in 1995. People had been farming in Puerto Rico for centuries. Why did it take until the end of the twentieth century for the farmers to give a name to a creature that preyed on their livestock?

Those who believe the Chupacabra exists have explanations for all this. One of the most popular theories involves the government of the United States.

According to that theory, the Chupacabra was created by scientists working for the US government. The scientists created an entirely new animal, using features of other creatures that already existed.

This idea is similar to the plot of the American movie

Species, which was released in Puerto Rico on July 7, 1995, when stories about the Chupacabra were already in the news.

The idea of US scientists conducting secret experiments in Latin America—those areas of the Americas where Spanish and Portuguese are spoken—is not new to many people who live there. That’s especially the case in the Chupacabra’s homeland of Puerto Rico, which is a US territory. The US Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service has conducted many experiments in Puerto Rico’s El Yunque National Forest, including tests related to atomic radiation. The government wanted to see what effect gamma radiation, a type of energy produced when an atom bomb is exploded, had on the plants there. Although many native plants survived, there is much scientists still don’t know about how these dangerous rays might have changed the forest, and the land surrounding it. The people of Puerto Rico were understandably angry.

The US government also stored and tested dangerous chemicals in Puerto Rico, including poisons that could seep into the ground and water and make animals and people sick. Many of these experiments were run out of a US navy installation in Vieques, which made local people unhappy about the installation’s existence and distrustful of anything that might be going on there.

With this history, it’s easy to see why Puerto Ricans could so easily believe that the mysterious creature killing their livestock was yet another example of the United States government using their home as a laboratory even when it put people in danger.

Copyright © 2023 by Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.