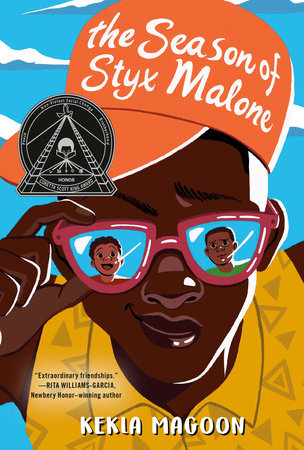

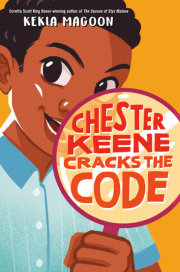

Extra-Ordinary

Styx Malone didn’t believe in miracles, but he was one. Until he came along, there was nothing very special about life in Sutton, Indiana.

Styx came to us like magic—the really, really powerful kind. There was no grand puff of smoke or anything, but he appeared as if from nowhere, right in our very own woods.

Maybe we summoned him, like a superhero responding to a beacon in the night.

Maybe we just plain wanted everything he offered. Adventure. Excitement. The biggest trouble we’ve ever gotten into in our lives, we got into with Styx Malone.

It wasn’t Styx’s fault, entirely. And usually I’d be quick to blame a mess like this on Bobby Gene, but no matter how you slice it, this one circles back to me.

It all started the moment I broke the cardinal rule of the Franklin household: Leave well enough alone.

°°°

It was Independence Day, which might have had something to do with it.

I woke up with the sunrise, like usual. Stretched my hands and feet from my top bunk to the ceiling, like usual. I touched each of the familiar pictures taped there: the Grand Canyon, the Milky Way, Victoria Falls, Table Mountain. Then I rolled onto my belly, dropped my face over the side of the upper bunk and blurted out to Bobby Gene, “I don’t care what Dad says. I don’t want to be ordinary.”

“What?” he said.

I knew he was awake. His eyes were open and blinking up at me. He had his covers pushed down and his socks balled up in his fist. He must’ve heard me.

“I said, I don’t want to be ordinary. I want to be . . . the other thing.”

“What other thing?” Bobby Gene said.

I rolled onto my back. “Never mind.” I didn’t really know what I meant, but it was on my mind because of what happened last night at dinnertime.

Dad got home from his shift at the factory around six, which was normal. He turned on the television, piping through the house the sound of news reports about things that were happening so far from here that they barely seemed real. The reporters were always blabbing on about economics and politics and the constant breaking news.

But every once in a while I would see something that made me want to reach through the screen and touch it, you know? Like to get closer to it, or to make it a little bit real. There was a story about dolphins one time. And a feature about a group of kids who sailed a boat around the world. Special things. Things you’d never find in Sutton.

The problem was, Dad was always talking about us being ordinary folks—about how ordinary folks like this and ordinary folks need that. He usually said all this to the TV, but our house isn’t that big and his voice is pretty loud so you can always hear him.

Ordinary folks just need to be able to fill the gas tank without it breaking them.

Ordinary folks go to church on Sundays.

Ordinary folks don’t care who you’ve been stepping out with; just pass the dang laws.

(A lot of times he said it more colorful than that, but I’m not allowed to repeat that kind of language.)

That night in particular he was getting all hot and bothered, as Mom would say. He was ranting at the TV and Bobby Gene and I were playing Battleship behind the couch. Sneaking back there was a tight fit for us, but we needed to practice undercover operations. Our ongoing spy game was the best thing we’d come up with for summer entertainment thus far.

If I could sink deep enough into the game, it felt like I could take on the whole world. Caleb Franklin, International Man of Mystery. A trench coat, a passport, dark sunglasses, and a briefcase of world-saving secrets. An important handoff, code-word clearance—

“Yahtzee!” Bobby Gene yelled. Which was what he yelled whenever he won at anything.

My spy bubble burst. The secret safe house dissolved. My shoulder ached from being squeezed into the couch-wall gap.

I didn’t have a passport. I’d never so much as crossed the Sutton town limits.

When the news went to commercial, the ad jingle was a piece of classical music. I popped my head up over the back of the couch. “I know that song. We played it in band. It’s ‘Tarantelle.’ ”

“Dinner!” Mom called. Dad turned off the TV.

“Hey,” Dad said to me. “You got that from just a few notes?”

I shrugged. “I like that music.”

“That’s because you’re extraordinary,” Dad said, patting my shoulder. “Let’s eat.”

My heart plummeted. I knew Dad thought he was paying me a compliment, since he loves to have ordinary this and ordinary that. Still, my heart sank. Extra-ordinary? Like, so plain and normal that it was something to be proud of?

I hated this. Hated, hated, hated it. Which is why I thought about it all night and into the morning. And why I vowed that, no matter what it took, I was not going to be so ordinary.

Copyright © 2018 by Kekla Magoon. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.