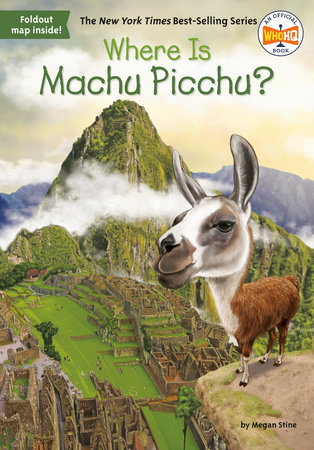

Where Is Machu Picchu? Flocks of green parrots flew overhead in the jungle. The air was sticky and damp. It was July 24, 1911. Hiram Bingham and six other explorers had been trekking through the jungles of South America for days. The thirty-five-year-old professor from Yale University was on a quest. He was searching for the place where an ancient people called the Incas had once lived and then died out four hundred years before.

Ever since childhood, Hiram had dreamed of a life of adventure. Now he was finally living it. He was leading an expedition that included a doctor, a naturalist, and a geographer. They were in Peru, where Hiram hoped to discover the ruins of the lost Inca city of Vilcabamba. He wanted to become famous.

The beauty of the jungle was breathtaking. Orchids bloomed everywhere. Snowcapped mountains towered above. Hiram and his fellow explorers followed a path along a river. They passed waterfalls and tree-size ferns.

Hiram later wrote, “I know of no place in the world which can compare with it.”

But after five days, some in the group were tired. They didn’t want to keep going. The journey had been hard. They were riding mules through a jungle that was overgrown with vines and buzzing with insects. Poisonous snakes slithered about. They decided to stay behind at the camp to wash their clothes or hunt for butterflies.

So on the sixth morning of the trek, Hiram set out with just one other companion—a sergeant from the Peruvian government. They were led by a local guide named Melchor Arteaga. Melchor had said that if they crossed the river and climbed two thousand feet up the mountain, they would find some ruins—ancient buildings that had fallen apart.

Could this be the magnificent city Hiram Bingham was looking for?

Hiram sort of doubted it. He had a rule for himself: Whenever someone told him fabulous stories of lost treasure, Hiram reminded himself that it might be just a story.

Still, he was curious. He was also determined and energetic. So he followed Melchor across a shaky bridge over rushing water. The bridge was made of only a few logs tied with vines. Melchor and the sergeant walked across the wobbly bridge, but Hiram felt safer crawling on his hands and knees. Then he followed the guide up a steep trail for more than an hour, part of the way on all fours.

By the time they reached the ridge of the mountain, Hiram and the sergeant were exhausted. And all they saw were some huts and stone walls. A few local people seemed to be living there. They offered Hiram water and cooked sweet potatoes.

The view from this spot was magnificent. Hiram could see down to the river valley far below. He could also see up to the snowy mountains high overhead. It was like living in the clouds.

But had he come all this way for nothing more than an incredible view of nature?

No. As soon as he walked a little farther and rounded a corner, he came upon something incredible. There was an entire city of ruins.

Hiram had not found Vilcabamba. Instead, he had found something much better—the hidden city of Machu Picchu (say: MAT-choo PEE-choo). It was an Inca city that no one in the outside world even knew existed.

Chapter 1: Who Were the Incas? Many hundreds of years ago, long before the time of European explorers, native peoples lived in tribes in both North and South America. They hunted, fished, grew crops, and sometimes fought. Their lives were simple.

But in the 1400s, in one area of South America, a tribe called the Incas did much more than that. The king ruled over a vast empire. Its capital was a city called Cuzco. There were roads and stone houses. The Incas created wonderful art. They learned how to work with metals like copper and bronze, and to make gold and silver jewelry. They wove special fabrics with fancy designs for the royalty. They studied the sky to learn about the sun, moon, and stars.

Although they didn’t have written language, the Incas kept records of everything. They used a system of knots tied on strings. These were called quipus (say: KEE-poos). With the quipus, they could keep track of how much land they owned. They also kept count of how many people lived in the Inca world.

The Incas believed that they were a special people, chosen by their gods. They worshipped the sun, and built stone temples for religious ceremonies. The temple in Cuzco was an incredible building, decorated with real gold. It was made out of stones cut so perfectly that they fitted tightly together, without cement or mortar.

Inside the temple was a golden statue of the sun god, named Inti. He was shown as a boy, with snakes and lions coming out of his body. Outside, there were life-size animal statues made of gold—monkeys, llamas, guinea pigs, jaguars, birds, and butterflies. All gold!

There was even a garden filled with life-size golden corn plants.

There were also niches inside the temples. Niches are indented spaces in a wall that usually hold a statue. But the Incas didn’t put statues in niches. On special occasions, they put mummies in them instead!

Whenever an Inca king died, his body was mummified. It was treated in a way that would stop it from rotting. The mummy was cared for as if it were still alive. People offered food to the mummy. They presented gifts to the mummy and dressed it in the best clothing, with gold and feathers. The mummy could then be carried around, from place to place, wherever the new king went. Servants were always nearby to keep flies away from the mummy. During ceremonies and rituals, the mummies were placed in the temple niches, a place of honor.

The Incas hadn’t always been a strong nation. In the early 1400s, the tribe was small and weak. But their city of Cuzco had great weather and good soil for growing crops. It made living there easy. A rival tribe called the Chancas wanted to live there, too. So the Chancas began marching toward Cuzco, planning to attack.

The Inca king was old and afraid. He ran away and hid. But his son was smart and strong. He quickly made friends with other small tribes and put together an army. They marched out to fight the Chancas before the Chancas could attack them.

The Incas fought a bloody battle with spiked wooden clubs. They won by capturing the mummy of the Chanca king. The Chancas thought they had no power without their mummy king. So they gave up. Then the Inca king’s son became the new king.

The young king chose a new name for himself—Pachacuti (say: patch-a-KOO-tee). It meant “earth-shaker” or “someone who turns the world upside down.” The new king had just done that—he had turned the world upside down by defeating the Chancas.

Pretty soon, he would shake—and shape—the Inca world even more.

Copyright © 2018 by Penguin Random House LLC.. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.