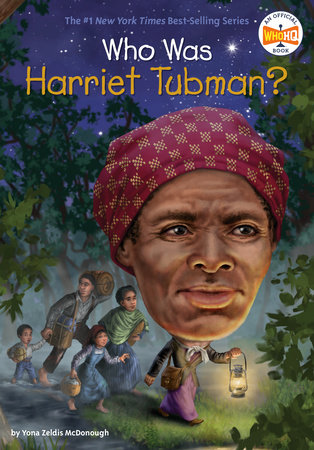

Who Was Harriet Tubman?

No one knows the exact year in which Harriet Tubman was born. It may have been 1820 or 1821. Most people didn’t think the birth of an enslaved person was worth remembering. Harriet Tubman would grow into a brave and daring young woman. She was brave enough to escape from slavery. She was daring enough to help others escape, too. Because she led so many to freedom, she was called “Moses.” Like Moses in the Bible, Harriet Tubman believed that her people should be free. And she risked her life many times to help them become free. Even after she had escaped safely from the South, she went back to take other slaves north to freedom. Here is her story.

Chapter 1: Life in Maryland

Sometime around 1820 in Maryland, an enslaved woman named Harriet Ross gave birth to a baby girl. Neither Harriet, who was called Old Rit, nor her husband, Ben, could read or write, so they couldn’t record the year of the baby’s birth. No one else thought it was worth doing. But Old Rit loved her tiny child and wanted to protect her. She hoped her little girl, whose nickname was Minty, would learn to sew, cook, or weave. Then she could avoid the backbreaking work picking crops like tobacco, corn, or wheat in the fields.

Old Rit and Ben had been born into slavery. They had many children, all of whom were also enslaved. Ever since 1619, when black people from Africa were kidnapped and brought on slave ships to Virginia, slavery had been a part of American life. By the early 1800s, most of the Northern states had stopped slavery. But the Southern states had not.

Enslaved people like Ben and Old Rit worked very hard, yet they were not paid for their work. Instead, Ben and Old Rit lived on land owned by their enslaver, a man named Mr. Brodas. This land and the many buildings on it was called a plantation.

Mr. Brodas’s plantation house was large and grand, like so many of those in the South. Ben and Old Rit could see the Brodases’ big house every day, but they didn’t live there. They lived in a log cabin, like the other enslaved people on the plantation. These cabins were very small. They had no windows. The floors were made of dirt. Piles of worn-out blankets were the only beds. Still, for little Minty, this was home.

As soon as she could walk, Minty joined her brothers and sisters and other enslaved children who were watched by an older slave. The littlest children weren’t forced to work—yet. There were even times when Minty and the other children could play and have fun. Summers were warm and bright. They swam and fished in the many streams and creeks.

Unlike many enslaved children, Minty lived with her loving parents. Her father told her stories about the woods. He could name the birds. He knew which berries were sweet and tasty.

Minty’s mother told her stories from the Bible. From her mother, Minty learned about Moses. Moses had lived thousands of years before. He led his people, the Hebrews, out of Egypt, where they had been slaves, and into freedom.

Around 1826, when Minty turned six, her life changed. Mr. Brodas hired her out. This meant that she had to leave her parents and her home. She had to go live and work for white people who could not afford to buy a slave of their own. The day she had to leave, a wagon came to take her away. Minty did not want to go. Her two older sisters had been sent away. She remembered how they cried and cried. But they had to go anyway. So did Minty.

Minty worked for a woman named Mrs. Cook. Mrs. Cook was a weaver. She spent her days in front of a big, noisy loom. Minty helped her wind the yarn. The air was filled with fuzz and lint. It made Minty cough. She couldn’t concentrate. She dropped the yarn. Mrs. Cook got angry. When she was angry, she would punish Minty by whipping her. Enslaved people were often beaten or whipped.

Mrs. Cook told her husband that Minty was stupid and slow. So Mr. Cook had her help him instead. He was trying to catch muskrats. He set out traps by the river. It was Minty’s job to watch them.

It was cold near the river. One day Minty woke up feeling sick. Mrs. Cook thought she was pretending so she wouldn’t have to work. Just as always, Mr. Cook sent Minty out to check the traps. She went down to the river, shivering from fever. When she got back, Mrs. Cook saw that she was really sick. She sent Minty home to her parents to get well. Old Rit took care of Minty for six weeks. But then it was back to Mrs. Cook and the loom. Minty could not do the job. The Cooks sent her home again.

Next, Mr. Brodas hired Minty out to a woman named Miss Susan. Minty, who was only about seven, had to watch Miss Susan’s baby. If the baby cried, Minty was whipped. At night she sat by the baby’s cradle. She rocked it gently. But Minty was tired. She would fall asleep and the baby would begin to cry. Then Miss Susan would get angry at being woken, and Minty was whipped again. Minty learned to stay alert for the baby, but it was hard. She was always tired.

Once, when Miss Susan’s back was turned, Minty reached for a lump of sugar that was in a bowl on the table. She had never tasted sugar. It looked so good. But Miss Susan saw her. Furious, she reached for the whip. Minty was too fast. Out the door she flew. She did not stop running until she was sure Miss Susan was no longer chasing her. But now what? If she went back, she would face a whipping.

Minty found a pigpen. She crawled inside to hide. She was very young, but she was bold. She tried to fight the piglets for potato peelings and other scraps of food. But the mother pig pushed Minty away.

After five days, Minty was filthy and starving. She knew she would have to return to Miss Susan. Later Minty would say, “I didn’t have anywhere else to go, even though I knew what was coming.”

Instead of being hired out again, Minty was sent back to Mr. Brodas. Now Minty had to work in the fields, which was very hard. She split logs, loaded wood onto wagons, worked the plow, and drove oxen. When she was out in the fields, Minty could see the sky and feel the wind. The others talked while they worked. That was how Minty began to hear new ideas. She heard people say they wanted to be free. Some of them escaped from the plantation.

They went north, to freedom. Others, like Nat Turner, started rebellions to end slavery. Nat Turner was caught and killed. But his ideas didn’t die. More and more, enslaved people thought about being free. Late one day in 1834, Mr. Brodas’s slaves gathered with those from another plantation to shuck corn. They sang while they worked, peeling the pale green husks from the golden ears of corn. One man stood apart. Minty watched him. He began moving across the big field. At first the overseer—the man who kept the slaves in line—didn’t notice. The slave was halfway across when the overseer saw him. He shouted for him to return. The man kept going.

The overseer followed, holding his big whip. Minty followed, too. The overseer was running now, chasing the man. The runaway ducked into a store. The overseer cornered him in the store, then called to Minty. He wanted her to help him tie up the runaway slave. But Minty didn’t move. She stood watching the two men. Suddenly, the man pushed past the overseer and was out of the store. Gone.

As for Minty, she blocked the doorway, so the overseer couldn’t follow him. The overseer picked up a heavy, two-pound weight and threw it at the runaway. The weight missed him, but it hit Minty on the forehead. She fell, unconscious and bleeding. She was brought to Old Rit, who nursed her tenderly. No one thought Minty would live. Still, Old Rit cared for her daughter night and day. Eventually, Minty recovered from the wound, though it left a scar on her forehead.

It wasn’t just the scar that made Minty different now. People treated her with respect. Although she was only thirteen or fourteen, she had defied an overseer. No longer was she called by her childhood name of Minty. Instead, she was called Harriet, her mother’s name. Clearly, she was not a child anymore.

Copyright © Yona Zeldis McDonough. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.