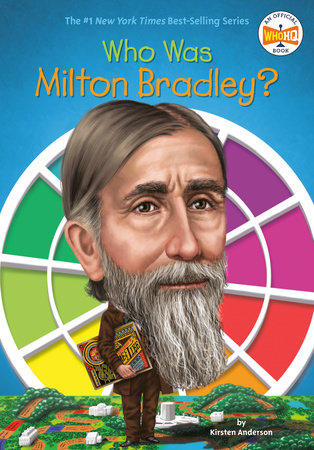

Who Was Milton Bradley?

One September evening in 1860, a young man stepped off a train in New York City. He had taken three trains to get there from Springfield, Massachusetts. Milton Bradley thought Springfield was a big city, but it was nothing compared to New York. The streets were crowded with people, horses, and carriages. Everyone seemed to be in a big hurry.

Twenty-three-year-old Milton noticed how the people were dressed. The women wore fancy hats with feathers and dresses trimmed in lace. The men wore tall hats and suits with shiny satin vests. Milton thought they looked like they were all wearing their Sunday best—and it wasn’t even Sunday! But he hadn’t come all the way to New York City to admire the fashions. He was there to convince people to buy and play a game.

The next morning, Milton bought a new hat and suit so he would fit in with the New Yorkers. Then he took a few samples of his game and walked into a stationery store. The store sold paper, pencils, and pens, plus small games and toys. He found the manager.

“How do you do, sir? I am Milton Bradley of the Milton Bradley Company of Springfield. I have come to New York with some samples of a new and most amazing game, sir . . .”

Milton showed the man The Checkered Game of Life. He explained how players moved across the red-and-white checkered board, making both good and bad choices about life. He said that people who loved games would find it entertaining. People who usually thought games were a waste of time would find it educational.

After sitting down with Milton and playing the game, the store manager bought all of Milton’s sample games. Milton returned to his hotel to pick up more. He brought samples to a different store. They bought them all. In only two days, Milton sold the hundreds of games he had brought with him.

Milton was thrilled and proud. He had believed that people would see themselves in The Checkered Game of Life. And he had been right. Milton was only twenty-four years old when he decided to put all his energy into becoming a game maker.

Over 150 years later, people are still playing games created by the Milton Bradley Company. And The Game of Life is one of the most popular board games of all time.

Chapter 1: Two Apples Plus Four Apples

Milton Bradley was born on November 8, 1836, in Vienna, Maine. His parents were Lewis and Fannie Bradley. Lewis was a carpenter and a factory worker.

The Bradleys never had much money, but they were a close, happy family. They were very religious. They went to church on Sundays and did not drink, dance, go to the theater, or gamble. But they believed in having other kinds of fun. They spent their evenings reading together and playing games like checkers or chess.

Milton’s parents were very involved in his education. When Milton was still quite young, he didn’t understand how to add or subtract. Lewis put six bright red apples on the kitchen table. He asked Milton to count them. Milton counted six. Then Lewis took away two apples. He asked Milton to count them now. Milton counted four. Lewis put back the two apples. Now there were six again.

Suddenly, Milton understood—the numbers in the math problem in front of him represented real things that you could count, put together, or take away. Using the shiny apples made all the difference for him. He thought this was a wonderful way to learn. Milton always remembered how his father helped him understand math by using apples.

When Milton was eleven years old, the family moved to Lowell, Massachusetts, so Lewis could take a job in a cotton factory. Milton attended the Lowell Grammar School and immediately became best friends with a boy named George Tapley. Milton was a serious boy. George was happy and cheerful. He could always make Milton laugh. They were a perfect pair.

Milton had a talent for drawing and decided that he would study art at the Lawrence Scientific School when he finished high school. Milton didn’t have enough money for Lawrence when he graduated from high school, so he went to work. He got a job in the office of a draftsman—a person who drew plans to build machines.

Milton earned extra money by taking a job selling paper, pens, and ink. Lowell was famous for its busy factories, and many people traveled far from home to find work there. That meant they all wanted to write letters home as often as they could. At night, Milton went to the boardinghouses where the factory workers lived, asking if anyone wanted to buy paper and pens. Milton was very successful. He wrote in his diary that the female factory workers bought more from him than the other salesmen because they thought he was funny and clever.

In 1855, Milton finally had the $300 he needed to attend the Lawrence Scientific School. But when his two-year art course was nearly finished, Milton’s father found a better job in Hartford, Connecticut. Milton reluctantly left school and moved to Hartford with his parents. But there weren’t any jobs for him in Hartford. Milton wanted to do

something—even if he didn’t know exactly what yet. Milton decided to try his luck in a bigger city: Springfield, Massachusetts.

Copyright © 2016 by Kirsten Anderson; Illustrated by Tim Foley. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.