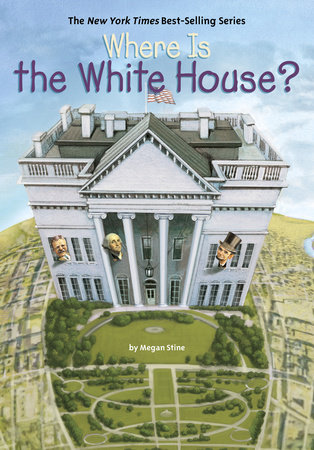

Where Is the White House?

On a fall day in 1792, President George Washington stood in a muddy pit on a barren rise of land. Rolling hills nearby were surrounded by woods. Cows and pigs grazed in the distance. No one lived anywhere near this beautiful wilderness overlooking the Potomac River.

Washington picked up a hammer and drove a stake into the ground. Then he drove another. And another. Those stakes told the workmen exactly where to put the corners and walls of a new house. George Washington was the first president of the United States. But he was also a surveyor—a person who measures land.

A whole new city was going to be built! It would be the capital city for the new country of the United States of America. The house at the center of it would be the new President’s House.

It would take eight years, many laborers, and tons of stone before the house was complete. George Washington never even got to live there. But eventually, the White House stood exactly where the first president said it should go, and the new capital city was named for him—the city of Washington.

Chapter 1: Building a Capital City

It was 1783. The Revolutionary War was over. The colonists had fought against the British for eight long years to gain their freedom. Finally, the colonists had won! A new country was born—the United States of America.

Now it was time to go about the business of creating a government. Like any other country, America would need a capital city. The city would need to have buildings for the government to work in. And it would need an important house for the president to live in.

Where should that capital city be?

At that time, some people thought the capital should be in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. After all, that’s where the first Congress met. It’s also where the Founding Fathers signed the Declaration of Independence.

But one day something scary happened. A mob of angry men stormed up to the building where Congress was meeting. Congress asked Pennsylvania to protect them from the mob. The governor of Pennsylvania refused to help. He thought the angry men were in the right!

That made the men in Congress think twice about where the capital should be. They decided it should not be in any of the thirteen states. It should be separate, on a special piece of land. Then the US government could have soldiers to protect and defend the capital city, without ever asking any state for help.

In 1790, Congress decided that the new capital city would be built along the Potomac River.

The spot they chose was part of Maryland and Virginia. Congress picked the spot to please the southern states. In exchange for having the capital in the south, the southern states agreed that the whole country should pay some debts from the war for the northern states. Now everyone was happy. Both Maryland and Virginia agreed to give up the land for the new city.

President George Washington hired a French architect named Pierre L’Enfant to design the city. L’Enfant had big ideas. He designed the entire city of Washington, DC, on a grand scale. The main avenues in the new capital would be wide. They would lead into huge traffic circles. There would also be long diagonal streets. Important statues and monuments would be lined up with one another. That way people could stand at one important building and look straight down the avenue to another one.

L’Enfant planned that the President’s House would sit at one end of a big diagonal street. The Capitol building, where Congress would meet, would sit at the other end. Straight across from the President’s House, he thought there should be a statue of George Washington riding on a horse.

L’Enfant drew up the plans and gave them to George Washington. Washington liked the plans, but not everyone agreed about the house. L’Enfant had set aside more than eighty acres of land for a “Presidential Palace.” Thomas Jefferson, one of the Founding Fathers, thought a big house was a bad idea. He said it would be too grand and showy. It would seem like Washington was trying to be a king—not a president elected to serve the people.

Jefferson said they should hold a contest to see who could come up with a design for the house. Washington agreed. So the contest was announced, and several people sent in designs. Some of the drawings looked like palaces or churches. One of them even had a throne inside. And one design was sent in anonymously—without a name on it. It was probably sent in by Thomas Jefferson! He very much wanted to help design the President’s House.

George Washington had his own ideas, though. He had already met a builder he liked. His name was James Hoban. Washington invited Hoban to enter the contest. He met with Hoban privately. They probably talked about what kind of house Washington wanted. And guess what? Hoban won the contest!

There was only one thing Washington didn’t like about Hoban’s design. It was too small! It was five times smaller than the palace L’Enfant had planned. So George Washington told the builders to make the house one-fifth bigger. He also told the workmen to add a lot of carvings of leaves and flowers around the front door, to make it fancier.

Many of the workmen on the new house were slaves who had been “rented” from their owners. They had to work for free. The slaves were good, strong laborers, but they weren’t trained to do carvings in stone. So workers were brought to America from Scotland to create the beautiful carvings on the front of the new house. Free African Americans also worked to build the house.

The house Hoban designed would become the White House—although it wouldn’t be called that for many years. When it was being built, it wasn’t even white! It was made from light brown sandstone—a kind of stone that has many tiny holes in it. If rain got in and then the water froze, the stones could crack. So the President’s House was immediately painted with whitewash to fill the holes.

George Washington died in 1799, a year before the house was completed. The father of our country is the only president who never got the chance to live in the White House.

Copyright © 2015 by Megan Stine. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.